Professor Jon Russ – Archaeometry Research

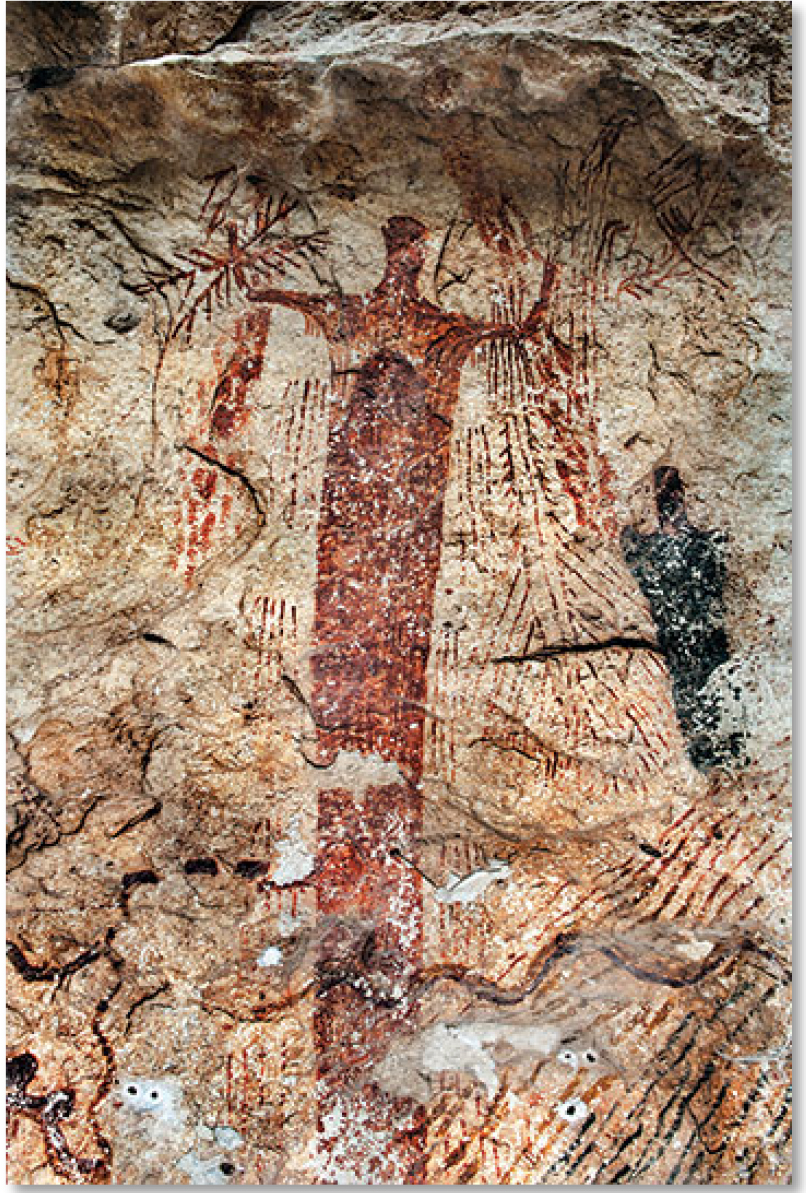

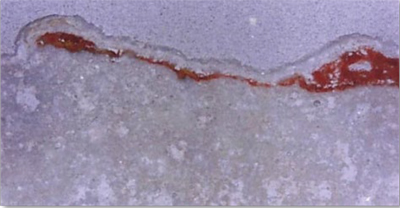

Nearly all prehistoric rock paintings found globally are encapsulated within natural rock coatings composed primarily of calcium oxalate. It is apparent that the oxalate accretions help preserve the artifacts by keeping the paints fixed to the rock substrate and preventing surface erosion. The oxalates are so prominent in rock art sites that radiocarbon ages of the coating is currently the primary means to establish the age of the ancient paintings. However, how the coatings form is still a mystery. Our studies involve the chemical analysis of the trace organic content in the coatings. These compounds are providing clues as to how the coatings form.

Residue analysis of prehistoric smoking pipes: Another research project is the chemical analysis of archaeological smoking pipes from North America. At the time of first contact with Europeans in 1492, tobacco was ubiquitous throughout the New World. Although the original ancestral source of tobacco is known to be the Andean Highlands, how and when tobacco became widespread remains uncertain. The techniques we use allow us to establish whether an artifact contained tobacco via the detection of nicotine in the residue. The artifact shown at right (FS 74) is a smoking tube recovered from the Flint River Archaeological site in Western Georgia that was radiocarbon dated at 3500 years old. We identified nicotine in this artifact, making it the earliest evidence of tobacco in North America.

Included in our studies are pipes that were used during religious ceremonies such as the Mother Earth Effigy Pipe shown here. Various plants were smoked in these pipes, and part of our challenge is to determine which plants were part of the smoking complex. To that end, we are analyzing plants and the byproducts of simulated smoking to characterize the compounds that result in the combustion of the plant material. This allows us to relate these characteristic compounds to the organic analysis of the pipe residues.