Textiles are something we interact with every day, but often give little thought to. In fact, textiles are a way in which we can connect to the people of the past. We even still utilize some of the same natural fibers that ancient people used to make clothes. Nowadays much of our clothing is made with synthetic fibers such as polyester and rayon, however before the industrial revolution all clothing was made with natural fibers: linen, cotton, wool, silk, and the like. The most prevalent natural fibers found in Ancient Greece and the surrounding areas are linen and wool. A textile found at the Lefkandi site in Greece offers a fantastic example of early iron age textiles and highlights the rarity of textile finds from this era.

Linen is a fabric made from the fibers of the flax plant and is revered for its breathability and moisture wicking properties. There is evidence that flax was domesticated during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages along with more widely known domesticated crops such as grapes and olives (Valamoti 2011, 558). The Greeks were able to create vastly different fabrics with the flax plant by harvesting it at different times, and developing techniques and technologies that allowed them to create extremely diaphanous linens and thicker, opaque linens (Spantidaki and Margariti 2017, 55).

Wool has also been a staple fiber among civilizations since the Neolithic era. It is a natural fiber derived from the fleece of sheep and is renowned for its insulating and moisture wicking properties. Wool is often thought of as a fabric meant to be worn only in cold weather because of its insulating properties, however it would have been suitable for many different climates with variation in the thickness of the fabric. Since the domestication of sheep, wool was a staple in the economy of the Bronze Age Mediterranean (Nosch 2014, 1).

Textiles are one of the rarest archeological finds. The further you go back in history, the more rare it becomes to find textiles. Unlike materials such as metal and ceramic, the natural fibers of textiles will break down over time. Many of the textile remains from Ancient Greece that have been preserved have been chemically altered either by mineralization or carbonization. Mineralization occurs when fabric is preserved via association with another object, most often metal. As the metal corrodes over time, the corrosion replaces the organic fibers of a textile. This is similar to the process that creates petrified wood in which silica replaces the wood and preserves the grain. Another way in which textiles are preserved but chemically altered is called carbonization. Carbonization occurs when plant or animal materials are subjected to high enough temperatures that they turn into carbon similar to the way charcoal is made from wood (Spantidaki and Margariti 2017, 51). Carbonized textiles are a common find at sites that were buried by a volcanic eruption such as Akrotiri and Pompei. An exceptional example of a mineralized textile was found within a bronze krater at the Lefkandi site

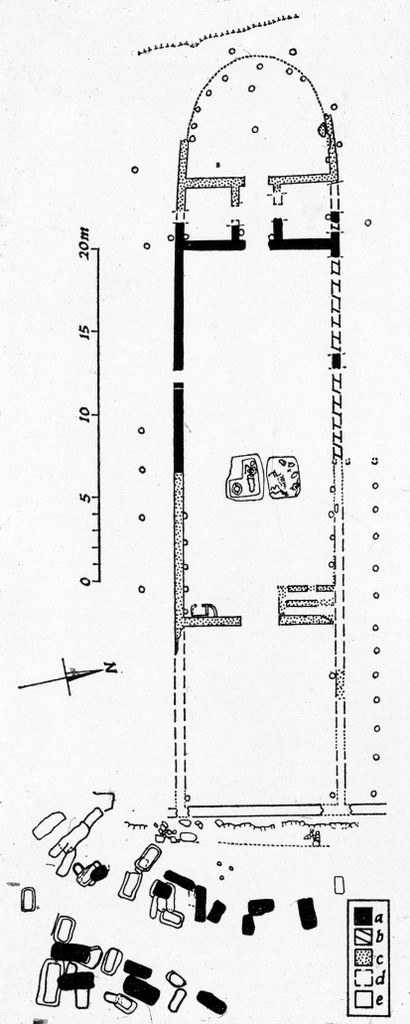

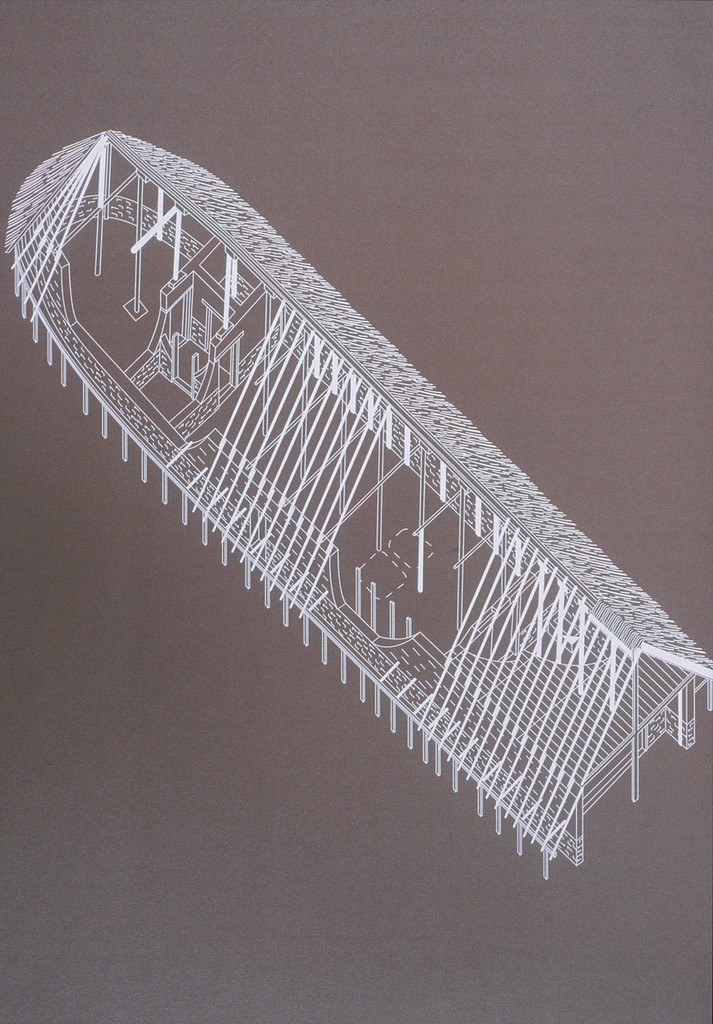

Lefkandi is an archeological site in Euboea that spans several centuries between the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. A reconstruction of the House at Lefkandi is seen in fig. 2. The purpose of the building is unknown; however it has been theorized that it is the possible location of a heroön, or a hero shrine (Stansbury-O’donnell 2015, 90). It is believed that this site is a heroön because it holds the graves of a man, a woman, several horses, and a rich collection of grave goods including a sword and spear beneath the floor of the house. The man was cremated, and his remains were buried in a bronze krater (fig. 1) along with a shroud (fig. 4) and two decorative strips (fig. 5).

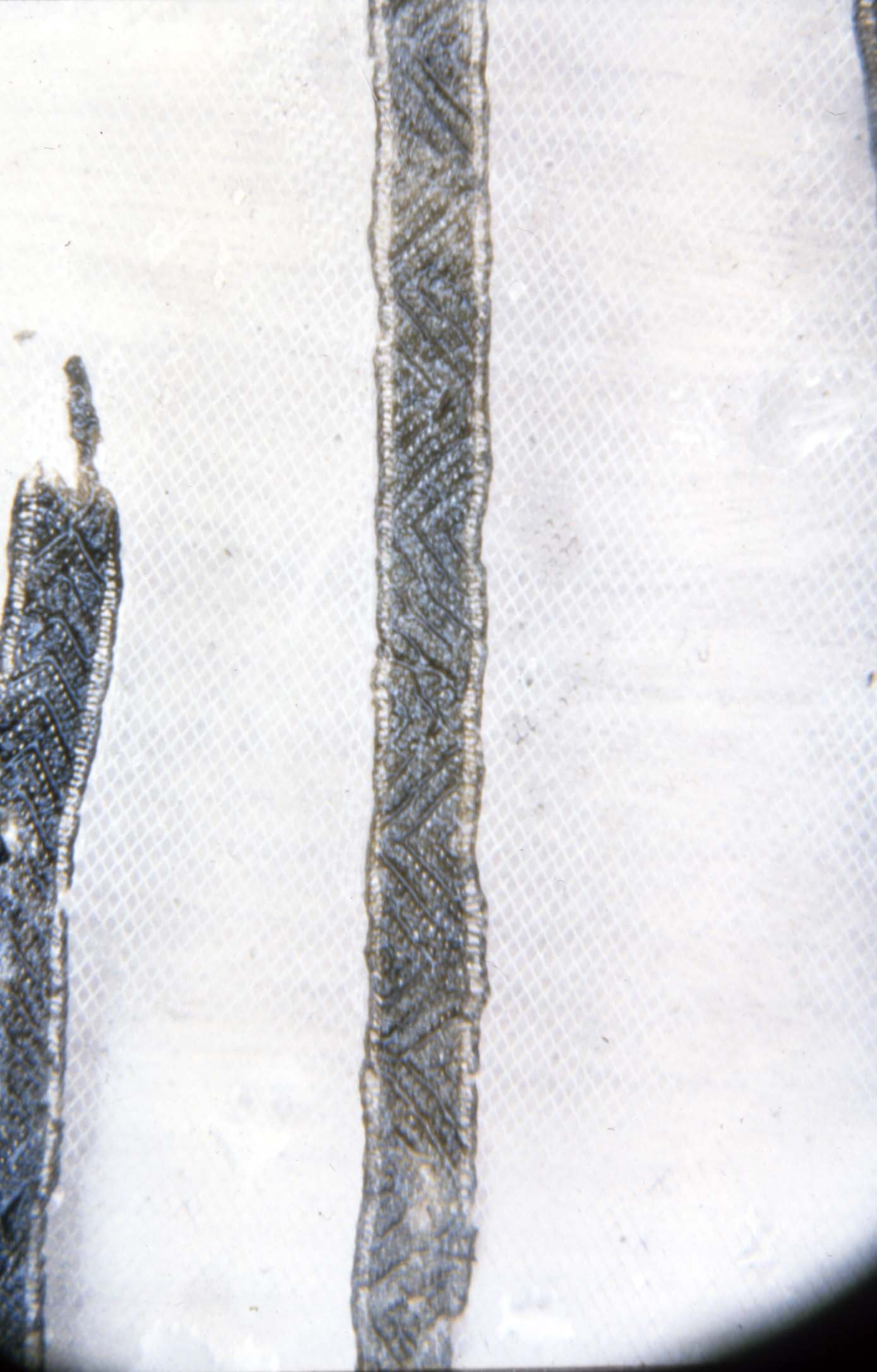

One of the two bands of fabric that was found with the shroud represents the change in clothing both in style and technology that was occurring near the end of the Bronze Age and beginning of the Iron Age. This band shown in fig. 6 is the oldest example of chevron linen twill tape (Spantidaki and Margariti 2017, 59). Chevron refers to the geometric zig-zag pattern displayed, and twill tape is a type of fabric with a weave of diagonal parallel ribs that is woven in long strips with either side finished off to prevent any fraying.

Despite the large number of textiles that would have been produced, finding ancient textiles is extremely rare, finding large swaths of them intact is even rarer. Textiles like linen and wool have been important in global and local economies since prehistory. The textile from the heroön at Lefkandi is an exceptional find and a testament to the types of fibers clothing was being constructed from and the complex situation in which an ancient textile is preserved.

Skylar Rutledge '25