Off the coast of Greece lies Crete, the fifth-largest island in the Mediterranean and home to one of the first European civilizations. Therefore, Crete is also home to some of the first Mediterranean art. Minoans, the ancient inhabitants of Crete, thrived off of the surrounding sea and set up multiple towns along the coast, making Crete an ideal spot for ancient maritime trade. During this time, Minoan influence boomed due to their central location in the Mediterranean. Their art and artistic styles were found everywhere from Greece to Egypt. The sea not only provided jobs and connection to ancient African, Middle Eastern, and European civilizations, but also gave them food and acted as a barrier between them and hostile societies.

The importance of the Mediterranean was an evident motif in Minoan art. Many vases and frescos from all sides of Crete depicted animals, sea battle scenes, and possible snapshots of Minoan rituals surrounding the sea. The Marine Style, a popular style of art in the Late Minoan period, completely revolved around depictions of sea life. In the 1970s and 1980s, Hugh Sackett, a notable archaeologist at the time, traveled across Greece to excavate ancient sites. He recorded all of his travels through photos, which included the island of Crete, its coastal cities, its sublime landmarks, and its art.

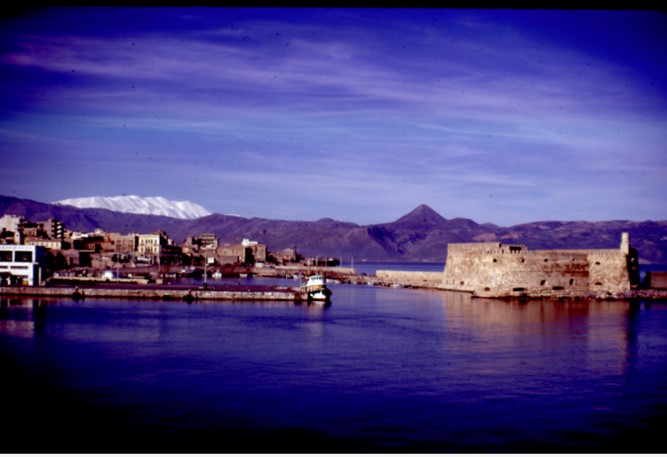

Just one of thousands of photos that archeologist Hugh Sackett captured of excavations from Lefkandi and Palaikastro is an image of the Gulf of Heraklion that overlooks 9th century C.E. Koules Fortress on the island of Crete. This image shows the vastness of just one of the oceans that the ancient Greeks frequently accessed. Due to its ocean-surrounded geography, the seas were major sites of trade as well as inspiration for Greek art. While Greek populations evolved, the surrounding oceans remained a constant influence on art, culture, and everyday life.

This photo shows a view of Mt. Ida, or "The Mountain of the Goddess", from across the Mediterranean Sea. It was taken in February of 1975 by Hugh Sackett. The Sea is relatively still and the color of the lighting indicates that it's likely either dusk or dawn. The twin peaked at Mt. Ida is a landmark on Crete and home to a cave where Ancient Minoans and even travelers from other regions would pray to their gods. The cave was a spot where earthquakes would shake violently, which probably led the Minoans to think that the earthquakes symbolized the power of the gods. Priests performed rituals for the "Zeus of Mt. Ida" who was born again every year in the cave.

Notably, the seas surrounding Greece were important for many reasons, but they were a large source of inspiration for artists on Crete in the last years of the Bronze Age, which can be seen in the stirrup style Marine Style Pilgrim’s Flask ca. 1500, that Sackett captured on film. Exuding naturalism, a faded octopus dominates the surface with tentacles scattered evenly throughout the space as if the creature is eternally fixed propelling itself through the ocean. Provenanced from Palaikastro, this piece is just one example of how an aquatic creature is celebrated in Greek art.

The Pilgrim Flask with an Octopus created in between 1500-1450 BCE, was found in Palaikastro, Crete, and now sits in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. It is a typical example of the Marine Style found in Late Minoan art. This pot is characterized by a black octopus that almost takes up the entirety of the pot and works to emphasize its curvature. Pieces of black coral, shells, and sea urchins reduce the negative space in between the tentacles. In fact, the entire pot seems to have some decoration, even at the mouth, whose decorations are more dilapidated than the bottom designs. This might have happened because the liquid could have worn down and dissolved the paint at the top. The name "Pilgrim Flask" was created because Christian pilgrims would often carry around a similarly shaped pot for holy water. Just like Christian pilgrims, Ancient Minoans most likely would've used this pot for liquids for religious ceremonies or rituals.

In these kylikes, there are outstretched tentacles of marine animals swirled in spirals around the body of the vase. The octopus shown in the bottom right kylix is in movement and shows off the artist’s talent to create an octopus that looks alive through its movements. The octopus takes up most of the space on the body of the kylike. These date back to the bronze age but are later than the two octopus jars above and come from the Greek mainland.

One of the most well-known and compelling structures from the Bronze Age is the Palace at Knossos, a hub for community and activity in Minoan culture. Although Knossos wasn’t on the coast of the Aegean Sea, the ocean still influenced many cultural aspects of the city. In its best years, the walls of this Minoan palace stood decorated with frescoes that served to emphasize the sophistication and beauty of the palace. In the Queen’s Megaron archeologists uncovered a fresco composed of dolphins and other smaller fish swimming above the room’s doorways.

This frieze, done in between 1700-1450 BCE shows dolphins and other marine life. Only two of the dolphins were preserved, so the others have been reconstructed. Some other details are spiral decoration motifs on the walls and rosettes, painted to indicate that the rosettes replaced the spirals in the painting. Although the dolphins swim in patterned lines, multiple fish swim around them giving more asymmetry to the piece. Sir Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who discovered the room, thought that the decorations and the overall size of the room meant it was for a woman and named it "The Queen's Megaron". Despite this room's name, there is no evidence that it was a queen's room of any sort.

The West House, which was built around 1550 BCE, displays multiple frescos on its walls. Many of them, such as this fisherman fresco, are centered around the ocean. The West House is found in Akrotiri, Thera. This fisherman was found on the middle level of the north wall in Room 5, but there was also one on the west wall that was found in a much more dilapidated state. The representation of the fishermen shows one aspect of how important the sea was to Minoans because without it, they would not have fish as a vital food source and would not have fishing as a career opportunity.

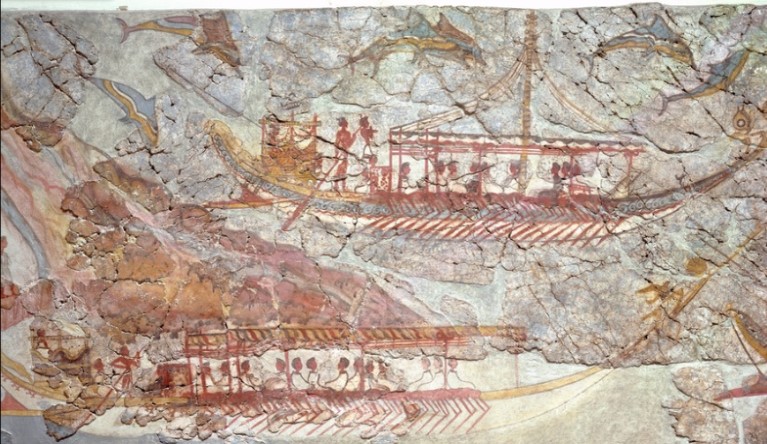

There are dolphins depicted with wavy lines to insinuate movement (Stebbins 1929). They are swimming alongside the ships to make the scene feel more alive and naturalistic. There is debate about the meaning of the fresco as it could depict a voyage or procession, but the goal of naturalism is apparent (Morris 1989).

This photo, taken by Hugh Sackett, shows a rooftop view of an unidentified town on the island of Crete in May, 1975. This town is built on a hillside spotted with trees on the coast with what looks to be a man-made, stone pier jutting out into the sea. Its proximity to the coast makes it an ideal trading spot and port city. There are no people in this photo, only residential houses on the coast and hillside and a church in the center of the image; most of the houses have a flat roof.

This image shows The Central Court in Phaistos, Crete. This Minoan palace was built around 2200-1470 BCE. On one side of the palace faces the Libyan Sea and the other, which is shown in the image, points away from the coast toward Mount Ida. This central court closely resembles the central courts of Knossos and Mallia: all three are similar in proportion and size. All three are also oriented from North to South, suggesting that the architects followed some sort of guideline when constructing these palaces or that the central courts served one, unknown purpose. Many archaeologists believe central courts could have been used for religious affairs, processions, military reviews, or bull-leaping events.

The later years of the Bronze Age, after the Minoan period, were defined by a shift towards more abstraction, but marine animals were still popular motifs. Small enough to easily overlook, archaeologists uncovered this Dress Ornament in the form of a Nautilus Shell, a small piece of gold jewelry. The shell alludes to the ocean and suggests that whoever donned the gold charm might have wanted a piece of the ocean close to them. Indeed, the seas seemed to touch many aspects of Greek culture.

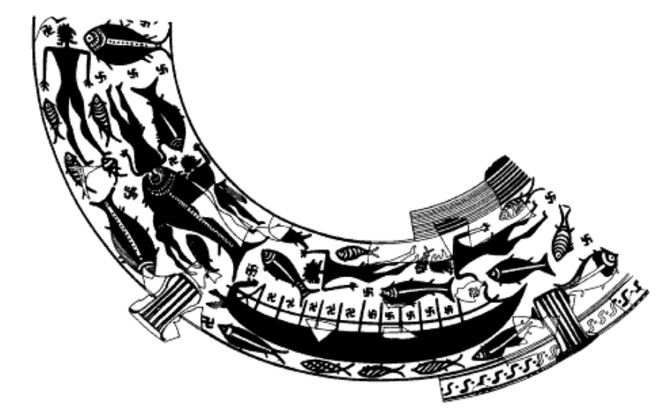

While the ocean brought ancient Greeks an abundance of artistic inspiration, there was also a dark side to such a vast and unknown entity. Perhaps a piece of pottery that highlights the fear of this dark side is the Late Geometric Krater from Pithakoussi of a shipwreck scene (Mountjoy, 1984). Believed to have been created during the late Geometric era, this krater emphasizes the power of the ocean by positioning men and fish of the same size next to each other. The men are positioned horizontally but still near their ship, suggesting they are recently deceased. Viewers of the art can only infer that the vast expanse of water that surrounds them is the cause of their demise.

Avery Comish '24, Emily Matusik '25, Kendall Dobie '24