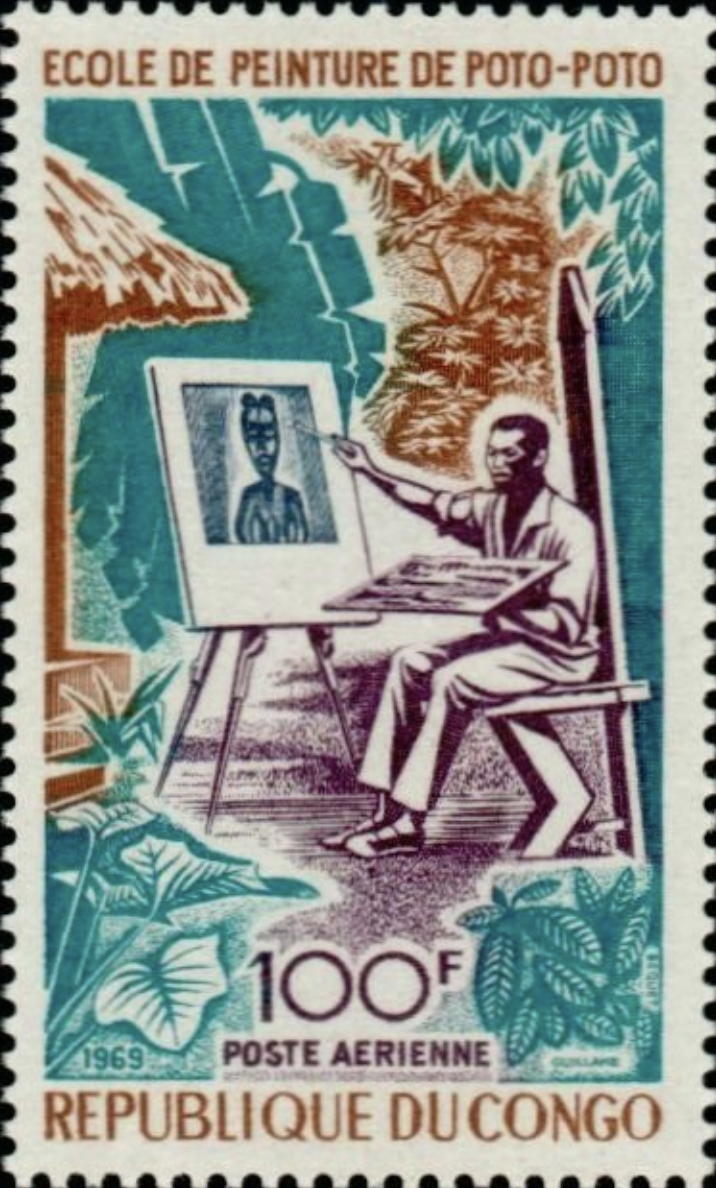

Pierre Lods (1921-1988), a young Frenchman and amateur painter, founded the Poto-Poto School of Painting, also referred to as the Centre des Arts Africains, in the suburbs of Brazzaville in present-day Moungali in 1951 following his move to Africa from the former French Indochina (now Vietnam). The school was named for the nearby Poto-Poto neighborhood that is now south of Moungali. Though the story is not proven to be true, Lods claimed that his inspiration for the school came from an experience with one of his servants, Félix Ossali, who Lods witnessed painting blue birds on a map in a style he had not yet seen in what he had observed of African art. Thrilled by Ossali’s vivid use of color and unique figurative style, Lods then invited Ossali and a group of his friends and relatives to paint in an informal workshop – the beginning of what would evolve into the renowned Poto-Poto School.

From the school’s inception, Lods’s primary ambition was to foster the natural talent of the African artists who had little to no background in painting or knowledge of the conventions of European fine art. He did not enforce formal courses or impose any specific discipline that would limit the artists’ imaginations. The artists were encouraged to work freely in oil and gouache from whatever inspired them, as long as it was authentic to their own culture. Because Europeans had historically dismissed African art as primitive, Lods aimed to counteract this assumption by providing African artists with a space to express their creativity and voice their experiences through art. Lods would purportedly only give a technical critique of an artist’s use of certain colors after a painting was finished, but the style and subject matter was left to the discretion of each artist.

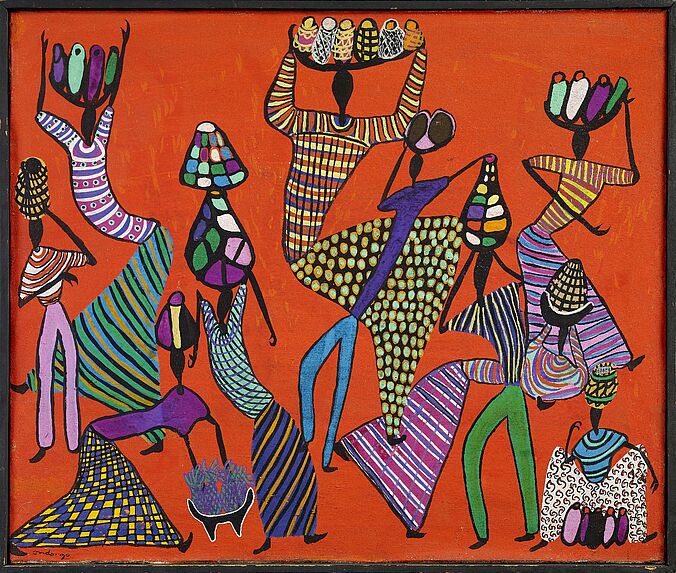

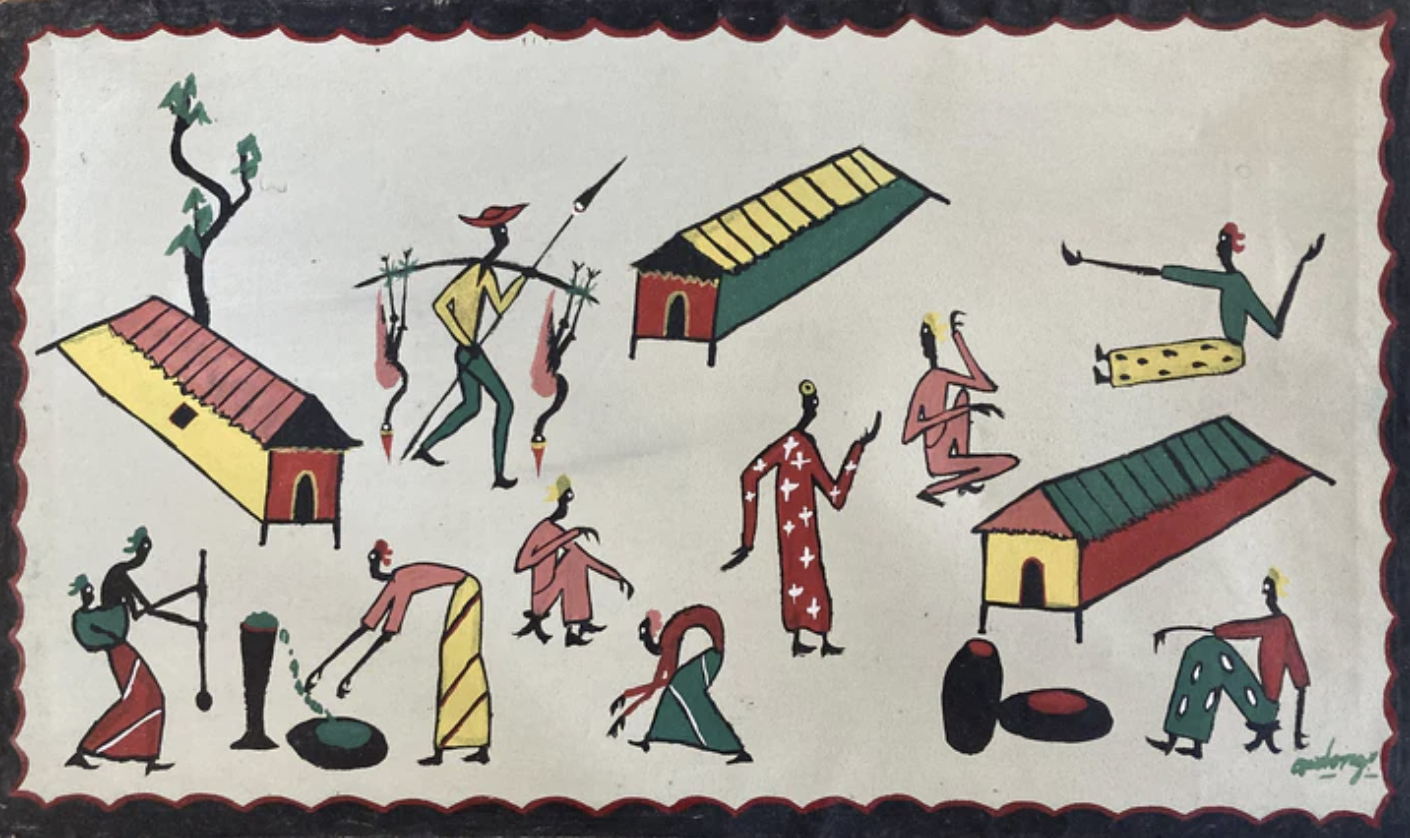

The artists of the Poto-Poto School produced varying styles that shared common themes from daily life in the Congo. One of the most prominent of these styles seen in the work of multiple artists is the “Mickeys” style, as seen in this collection of paintings. This style, most popular in the 1950s, was first seen in Ossali’s work. It is characterized by simplified figures composed of black lines implying movement that recall animation sketches. They are thus referred to as “Mickeys” as a reference to Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse animated character.

The Poto-Poto School held numerous exhibitions across the world throughout the second half of the twentieth century, including at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1956. American audiences categorized the paintings as “avant-garde," though the Poto-Poto artists would not have been aware of contemporary European and American art movements. In fact, canonical Modern art – Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism – had taken inspiration from African visual culture.

After the French and Belgian Congo gained independence from their respective European colonial powers in 1960, Lods left the school to teach artists in Dakar, the capital of Senegal, at the insistence of the country’s president Léopold Sédar Senghor. The artists formed a cooperative to continue operation of the school under the guidance of former students Nicolas Ondongo and Guy Léon Fylla. The Poto-Poto School continues to operate in this manner as former students become the teachers of each new generation, preserving the legacy of Lods’s teaching style that encouraged individual development of personal style and celebration of Congolese culture.

Nicolas Ondongo

One of the most notable artists trained at the Poto-Poto School was Nicolas Ondongo (1933-1990), who was also one of the first students recruited by Lods alongside Félix Ossali. Lods took Ondongo to France in 1949 to be a servant for his mother, and after their return to the Congo, the two found the location upon which they would build the Poto-Poto School. As an original student under the guidance of Lods, Ondongo was trained with little direction or influence from European ideas of art, and instead he developed a style informed by his own experiences.

Ondongo gained international recognition for his work throughout his time at the Poto-Poto School. He received an award on behalf of the Central Congo at the Eighth National Exhibition of Labour in Paris in September 1955, and he received another diploma and gold medal at the Tenth National Exhibition of Labour in December 1961.

In 1962, Ondongo became the head of the cooperative founded at the school following Lods’s departure for Senegal in 1960, and he continued to live on the school grounds and teach the second generation of artists in the same manner as he was taught by Lods.

Website Bibliography

Center for Preventative Action. 2023. “Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo.” Council on Foreign Relations.

https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo. Eckstrom, Kevin. 2002. “Presbyterian Church Mulls New Rules in Sex Abuse Cases.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/10/05/presbyterian-church-mulls-ne w-rules-in-sex-abuse-cases/4f9781fd-47c8-414c-8e78-a3f41e799235/.

Kamanda, Kama S. 2012. “The Song of Resistance.” National Poetry Library. https://www.nationalpoetrylibrary.org.uk/online-poetry/poems/song-resistance.

Mbon, Parfait. 2022. L'école de peinture de Poto-Poto: une tradition créative à l'épreuve du monde. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Scanlon, Leslie. 2010. “PC(USA) named in lawsuit by alleged victim of sexual abuse on mission field in 1988.” Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). https://www.pcusa.org/news/2010/12/16/pcusa-named-lawsuit-alleged-victim-sexual-abu se-mi/.

Tati-Loutard, Jean-Baptiste. 1978. “The Poto-Poto School of Painting - Congo.” Africa Quarterly 18, no. 1 (July): 24-33.