In Western Eurocentric spheres, politics or the visual arts are incomprehensible without looking to the Greeks and their lasting legacy; Greek thought was the precedent to many ideas relevant to and making up modern society. Scholars for centuries have referenced Greece as the most influential country in terms of cultural impact on the modern era, noting that "the modern study of ancient art and the making of modern art are inextricably intertwined” (Douglas 1813 and Prettejohn 2012).

Admired for its rational proportions and idealized beauty, Greek classical and Hellenistic art and architecture was first proliferated and adopted by the Romans through their mass number of marble copies of Greek originals. These classical ideals were then “reborn” during the Renaissance era, where 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th century thinkers and artists rediscovered classical texts and embraced Greek idealization and the “perfected” body as it pertained to the movement's budding emphasis on the individual. This persisted into the Neoclassical period during the second half of the 18th century, where the creators of the modern nation state were inspired by the Greek ideals of democracy, rationality, and heroism which was thought to be reflected in the resulting classically-derived art and architectural forms.

Some of these neoclassical thinkers from across Europe became particularly interested in the Greek War of Independence between 1821-1829, maintaining the belief “there existed an earnest moral obligation for Europe to restore liberty to Greece as a kind of payment for the civilization which [Greeks] had once given the world" and that "hereditary nobility of mind and feature persisted stubbornly among the Greeks in their polluted, Ottoman environment" (Cunningham 1978). The most popular Philhellene (a term for a lover of Greek culture), the Romantic English poet Lord Byron, came to Greece and mobilized efforts from across the Western world to help the Greeks escape Ottoman rule.

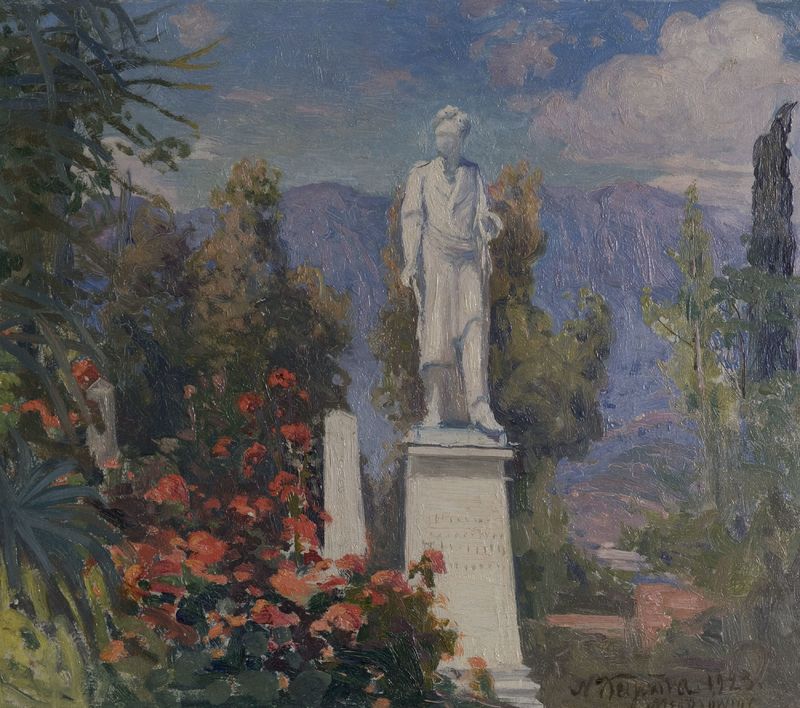

The Garden of Heroes in Missolonghi, Greece, as pictured here by Hugh Sackett on the Greek Day of Independence in 1977, pays homage to and memorializes those who dedicated their lives to the liberation efforts. These sculptures in the Garden of Heroes can identifiably be placed within the Greek visual tradition as they directly reference classical works and exemplify the stereotypical Greek trope of the immortalized hero.

This particular image allows us to see the large scale of these monuments in comparison to people who stand on the stone-pathed areas in the garden of heroes. The height of these memorials demand the viewer to “look up” physically at the heroes, playing on the notion that the viewer will also “look up” to these figures in admiration similar to Greek tradition of hero worship, and how the Western, philhellenic culture "looks up" to Greek culture as well (Reid 2017).

This slide shows a more detailed and up-close shot of the Lord Byron monument, or as Sackett refers to it, Heroön. A heroön was a shrine dedicated to a hero in ancient Greece, often placed where the hero was buried. Sackett, who excavated a possible heroön location at Lefkandi, refers to this statue of Byron in this way because not only is Byron revered as one of the heroes of the Greek revolution, but it’s also legend that his heart remains in Missolonghi where he died (Cunningham 1978).

This Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic bronze original, demonstrates the Hellenistic baroque artists' desire to now portray realistic emotions to match the mastery of rendering of the body. This dying Greek enemy appears helpless as he bleeds out his right side and looks to the ground in dejection. Roman copyists have noted that they wanted their viewers “to step mentally into [the subject’s] shoes” (Stewart 2014). All of these elements produce a certain humanizing effect that classically trained artists in the centuries to come draw inspiration from.

To the right is Sackett's slide of the memorial and tomb of another Greek hero in the war for independence, Markos Botsaris. The subject of this sculpture is quite different from the Dying Gaul, as we see a young girl mourning the hero. The French philhellenic sculptor, David d'Angers, obviously employs a nearly identical posture and tragic attitude, though. Both figures are curled up and nude, which exhibits both the Greek emphasis on the idealized body as well as vulnerability. This sculpture illustrates “the marble is no mere relic of antiquity, locked in the past, but has the power to produce a physical response in the modern observer," showing the lasting cultural impact of Hellenistic art and its reception in the modern era (Prettejohn 2012).

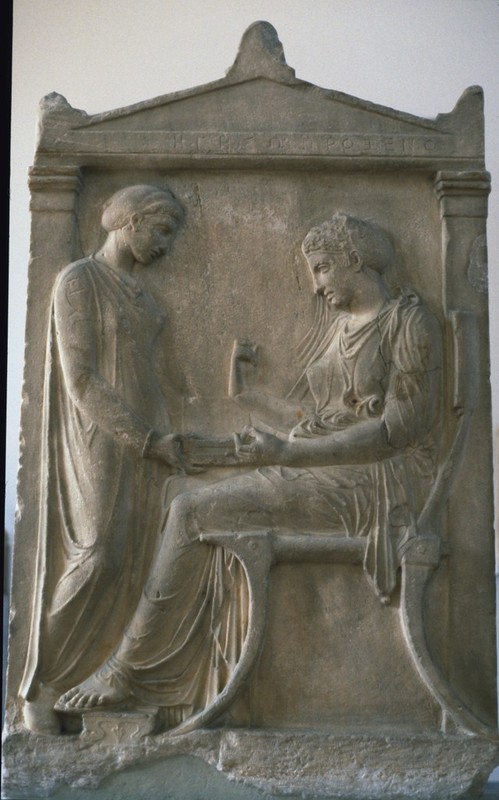

The correlation between these two pieces of statuary directly showcases the impact of Greek ideals and forms on modern sculpture, and in this case, relief sculpture that commemorates the dead. The image on the left is a high classical grave stele of a Greek woman, Hegeso, who is seated, opening a jewelry box in front of her servant. Although she wears clothes, her drapery closely follows her form, keeping true to the Greek awareness of the body’s proportions. This is also seen in the foreshortening of the foot that breaks free from the two-dimensional plane. There is also a quiet, solemn energy about this sculpture that reflects the funerary context of this commission and reveals Greek awareness of tone and emotion within their art (Zucker and Harris 2015).

Like the Stele of Hegeso, this memorial commemorating United States soldiers in the Garden of Heroes follows the same classical tradition, indicated through the relief techniques (note the similarity in feet). In both sculptures, the cut of the stone mimics the structure of a house, the drapery clings to the body, and the facial features are similarly rendered, which also gives this a forlorn tone. While the forms are more classicising, this piece also carries on the Hellenistic device which personified places through the utilization of symbols (Hind 2007). This woman is an identifiable representation of the United States due to the national bird, the eagle, that flies above her helmeted head.

The image to the left is of the Italian memorial in the Garden of Heroes, dedicated to the fallen Italian soldiers who participated in the Greek War of Independence. This memorial is very different from the others as it is not a stele or statue of a hero. Instead, the artist of the memorial decided to create a replica of a Greek column. The Italian memorial seems to resemble Doric columns, specifically the modified versions (Jones 2001, 698). The shaft of the column fits ancient Greek columns as the shaft is fluted, or long vertical grooves along the column. Although the top is cropped out of the image, the lack of base for the column-like memorial proves it to be that of Doric order. One can imagine that the top of the column may also resemble the top Doric order (i.e., necking, abacus, etc.) The reasoning for the design of the memorial could be to show how Italy was a support, like how columns are the support for the buildings.’ Regardless, choosing a column for Italy’s memorial may hold some meaning that characterizes the soldiers who dedicated their lives to the War of Independence.

The Parthenon, to the right, is an example of the temples that use Doric order for the columns. Constructed between 447 and 432 BCE, the Parthenon is one of the more famous temples in Athens and was the first large temple built completely from marble. The temple is a part of the Acropolis, a large complex of temples and monumental buildings. Though they are modified, the columns are of Doric order (Waddell 2002, 16-17). The Italian Memorial closely resembles the columns of the Parthenon as the columns of the temple and the memorial share some features. The obvious observation is that both are of Doric order. Along with this, both columns are not very thick and close to the size of Ionic order columns. From the comparison of the columns, the artist for the Italian Memorial may have drawn some inspiration from the Parthenon or may have wanted to reference the Parthenon as it was a temple built for the victory of the Athenians over the Persians.

Woo Wade '23 and Olivia Evans '23