Peak sanctuaries are a staple throughout the landscapes of Minoan Crete. These locations were a vital part to ancient societies and are extremely important to how historians today can better understand the people from earlier times. The concept of these sites was originally discovered by John Myres, a British archeologist, during his excavations on the mountain peak of Petsophas near Palaikastro in 1903. The term was later used by another British archeologist, Arthur Evans, during his own excavation at Mt. Yiouktas in 1909. From 1950 through 1980 Hugh Sackett was on his own archeological survey throughout Crete, where he had the opportunity to photograph many of the most famous sites that hold the title of a true peak sanctuary.

In his own writing, archeologist Alan Peatfield explains his thoughts on peak sanctuaries and their long journey to becoming a site recognized as separate and unique from others. In his article, The Topography of Minoan Peak Sanctuaries Revisited, Peatfield writes about another archaeologist and peak sanctuary connoisseur, Bogdan Rutkowski, with whom he agrees on the importance of these sites. The two archaeologists believe that the definition of these sites should stray away from the vague categorization and be given specific criteria instead. Rutkowski began to criticize those who labeled sites as peak sanctuaries when the sites in question were upheld with inconsistent characteristics. Peatfield writes that there are a few main factors that should be taken into account when deciding if a site should be labeled as a true peak sanctuary,

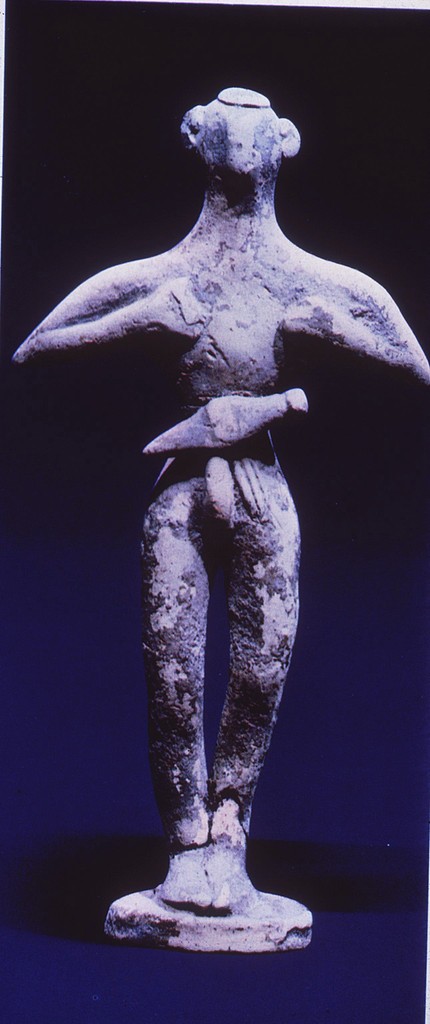

The first and most obvious factor is the placement of the site, which Peatfield writes must be on top of or close to the summit of a mountain and have a noticeable accessibility from and proximity to areas of human settlement and activity. The next factor is researching the topography of the site. To do this, archaeologists such as Peatfield use GIS (geographic information system) technology to help obtain a better look at the different layers of earth at these sites. When looking at these locations using GIS, archaeologists search for signs of human activity through the manipulation of the landscape. One of the final factors discussed by Peatfield is the existence of clay figurines. These figurines range from humans, separated limbs and body parts, to animals. The main thing archaeologists take into account when excavating possible peak sanctuary sites is the number in which the figurines appear. Peatfield explains that a true peak sanctuary site is defined partially by the immense amount of clay figurines that are excavated.

Many of these sites now classified as true peak sanctuaries were discovered long ago. Peatfield writes that the lack of new peak sanctuaries being identified is in part due to the strict criteria and standards all potential peak sanctuaries are held to. Peatfield's article helps create respect for these unique sites, emphasizing that every aspect of the location is important when discovering more about the usage of these sites by ancient peoples.

One important work of Minoan art is the Peak Sanctuary Rhyton, which depicts a peak sanctuary. The rhyton shows vegetation and wild goats in a flying gallop position to indicate nature. The peak sanctuary itself, shown near the top of the rhyton, shows a tripartite shrine with a wall. The door is decorated with spirals, and atop it are wild goats sitting and facing each other. It also shows horns of consecration, a religious symbol possibly based on the horns of bulls and found extensively in Minoan iconography, and three altars in the sanctuary courtyard (Huebner 2003).

Layout and Setting of Peak Sanctuaries

Religious Practices

The peak sanctuary site of Archanes-Anemospilia on the summit of Mt. Yiouktas is one of the most famous locations for the study of Minoan cult religions and their practices. The temple was unfortunately destroyed in an earthquake, which caused lamps to fall resulting in a simultaneous fire. It was not until the summer of 1979 when on-site archeologists Yannis Sakellarski and Efi Sapouna-Sakellaraki came across horns of consecration and began to dig. From that point on, the objects and information began to flow, with the excavation of a corridor and three rooms. In the corridor the Sakellarkis and their team were excited to have discovered a male skeleton.

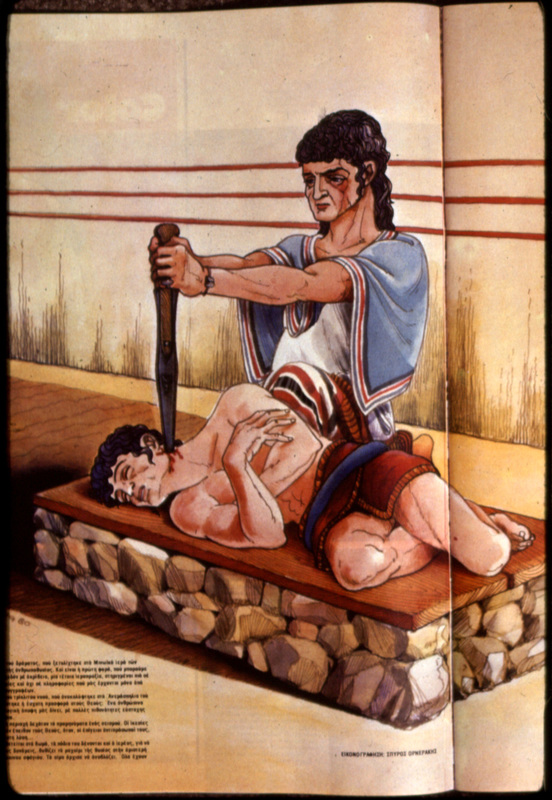

Based on the large pedestal and fragments of pottery found, the central of the three rooms is believed to have held the cult statue of the temple's main deity. The room to the East is believed to have been a storage for offerings to be organized before being brought into the center room. The room to the West was home to three more skeletons, two male and one female. The West Room also housed an altar and ceremonial bronze knife, both most likely used in ritual sacrifices.

What Happened in the West Room?

The West room at Archanes-Anemospilia is possibly the most infamous site for Minoan cult religions as some archeologists, such as Dennis D Hughes, believe it provides some of the best archeological evidence for human sacrifice. While the female skeleton was too far away from the altar to have been an active participant, the two male skeletons paint a different picture. The skeleton next to the altar was in his thirties or forties with a strong 6ft build, meanwhile the skeleton found on the altar, and possible victim, was only eighteen and had a much smaller height at 5ft 5. The ceremonial bronze knife discovered is also said to have been resting on top of the younger skeleton's abdominal structure. While the falling of the knife or even of the younger male onto the altar could have occurred during the commotion of the earthquake, Hughes provides an eerie piece of information in his book Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. In his writing, Hughes explains that with the simultaneous fire the bones of all three skeletons should be burned black. But the bones on the altar remained a white color, a phenomenon that only occurs when a body had been drained of blood.

Votive Figures and Offerings

The votive offerings found at peak sanctuaries are either luxury objects, made of more valuable materials and with greater detail which often incorporate religious iconography tied to the official Minoan cult religion which developed along with the palaces, or more modest offerings, often handmade clay figures. This indicates that the peak sanctuaries were visited by both commoners and the wealthy equally, and both were able to leave offerings. Offerings entirely unique to peak sanctuaries include figures of animals most commonly viewed as pests, indicating that these offerings were made to the deities as a request of protection against the pests (Dietrich 1969, 267).

Votive figures and fragments found at peak sanctuary sites help archeologists create a more clear picture of ritual practices that occurred on these summits. Just as Peatfield explained, there is always a large number of clay figurines found at every site that earns the title of a true peak sanctuary. Christine Morris writes an article about the individuality of the bodies depicted by votive figures throughout Minoan Crete. Here Morris explains that male figurines display a greater sense of individuality and value over that of females due to the increased variety of dress, accessories, and material. There is also a greater number of male figurines excavated from each peak sanctuary, making them more popular and possibly more important to religious cults.

The sanctuary at Petsophas near Palaikastro provides historians with clay figures that define an entire genre of Greek votive statues. As Morris writes in her journal article, Configuring the Individual: Bodies of Figurines in Minoan Crete, the figurines found at Petsophas like the "Belted Warrior" were the first to use the body position with the arms folded in towards the body. This pose is seen in the "Palaikastro Kouros" and other well known religious Cretan statues.

Maisie Arlotto 24', Elizabeth Acree '25