On the island of Crete, off the coast of Greece, there stand the ruins of the palace of Knossos (pictured above). The Minoan inhabitants dotted the island of Crete with palaces; however, Knossos is known for being the largest and longest-lasting palace on Crete. The ruins that we can see standing today date back to around Middle Minoan II (circa 1800 BCE, Hood, S, et al). While it originates from around MMII, the palace itself was inhabited well into Late Minoan IIIA (circa 1300 BCE).

The exact purpose and function of the palaces are not entirely known yet. Nevertheless, what scholars infer is that the palace served as a center of either political, religious, social, or economic power, if not a combination of some or all of those qualities. Minoan palaces are focused around a court that seemed to allow people from the town below to gather. On a wall fresco at Knossos, many people gather around what can be assumed is the central court watching an event happen. On our walk-through of the palace, we will discuss many other areas that could shed light on its purpose (Dreissen).

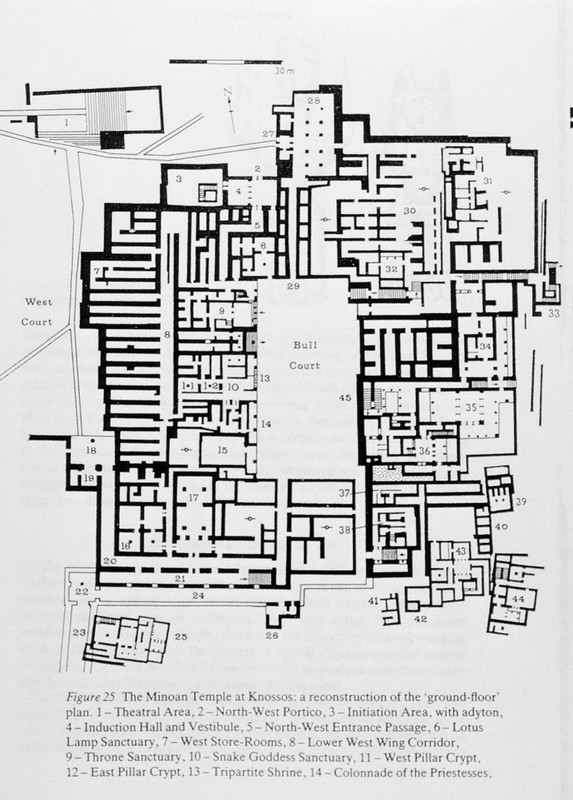

The Palace is known for its association with King Minos, the mythical lord of Crete, who was a son of Zeus and reportedly housed a "Minotaur" (a creature with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull) in his Palace (Farnoux, 1996). Arthur Evans's work shows that the Palace covered an enormous surface area of about 13,000 square meters and grew on a helicoidal (spiral or helical) pattern, which started from its famed central courtyard and developed over 20 different levels (D'Agata, 2010). At the peak of its splendor, the Palace displayed a "ziggurat-like" profile: something like a terraced pyramid on many receding levels (Farnoux, 1996).

Within Hugh Sackett’s catalog of photos, there are some photos of the palace at Knossos. Sackett had a long history with the site. He was a teacher for the Groton School in Massachusetts and first began excavations of the site with colleagues in 1960. He continued excavating the site on and off until 1973. After ‘73, he published his and his colleagues's findings on the unexplored mansion near the site. On these excavations, he would bring students from Groton to participate and was considered a great leader who kept the site constantly moving and motivated (Cadogan).

We will start with the theater area labeled 1 on the plan below in our walk through the palace. From there, we follow the parallel lines, which lead to number 27. These lines represent the Royal Road. From 27, we will proceed to 29, which is the north entrance passage that will also lead us straight into the bull court. The throne room (9) is on the right, and from the throne room, we will turn southeast and finally proceed to number 36, the Queen’s Megaron.

Royal Road of Knossos

In 1960, Sackett was placed under the excavator, Sinclair Hood, to test Arthur Evans’s dating system by excavating the royal road. The excavation shed light on some of Evan’s assertions about the occupation of the palace. Most importantly, there is little evidence of occupation in Early Minoan III (circa 2300 BCE). As one would follow the road, they would pass the theatre area to their left and the west court to their right. The road itself connected the palace’s north entrance with the town around it. (Hood 1962)

Image of the theatre area from the Palace of Knossos (Sackett 173).

Theatre Area of Knossos

First excavated in 1901 under the archeologist Arthur Evans, the theatre area stands at an interesting place for the palace. Evans called it the “converging point” of different pathways. Looking at the map, the theatre connects the northern entrance and the west court and entrance. However, while the theatre could act as a converging point, its purpose was isolated to just performance and not everyday use. The theatre could seat people for events by having tiered steps; these steps could either be sat or stood on. The exact nature of these events is currently unknown; however, scholars speculate that Minoan ceremonial dance took place here. (Evans 1902)

North Entrance Passageway

At the end of the royal road lies the northern entrance of the palace. Following the road inside, a room of pillars and a passageway leading to the central court greets the onlooker. This passageway is called the North Entrance passageway; it is famous for housing the Bull Leaping Fresco. The image used to the left shows the passageway from the direction of the central court; therefore, the top of the ramp would be the pillar room. Additionally, scholars found deposits of tablets from the Minoan occupation of the palace in the passageway and chambers around it. Unfortunately, these tablets remain undeciphered as we have yet to crack the language. (Woodard)

The Central Courtyard

A large, open courtyard greets visitors after walking out of the entrance passageway. On the right/western side, there would be rooms leading off of the courtyard into the palace. These rooms include the throne room. Directly south, there would have been two paths that led to the western and southern entrances. Finally, on the left/eastern side is the grand staircase and other paths that would have led deeper into the palace. Courtyards are the marker of traditional Minoan palaces. For Knossos, most scholars believe the courtyard was the site of bull games (hence the name bull court on the map) as well as being used for religious rituals. Scholars also agree that Minoan palaces were built around the courtyard, making it important in some way to the Minoans. In the image used to show the courtyard, the building in the background to the left is the throne room. (Driessen)

The Throne Room

After entering the courtyard and turning to one’s left, they can see the bathroom. The room consists of a bowl in the middle of the room with walls decorated by landscape frescos. In the room behind this is the actual throne room. On the East wall sits the throne, and a basin sits opposite of it. The reconstruction of the decorations of the throne room and the bath room are controversial. When Evans first excavated this site, he mixed up pieces of fresco paintings from both rooms, causing the originality of the frescos to be muddled. However, scholars have confirmed that the frescos had images of plants, landscapes, and griffins. The griffin is a significant image as it is one of the first portrayals of a mythological creature in Greek art. (Galanakis, et al)

The Queen's Megaron

At last, is the Queen’s Megaron. This room is mainly known for the dolphin fresco. The fresco seen in the image is a recreation, and its meaning is still not entirely understood. Additionally, while Evans called this chamber the Queen’s Megaron, there is no evidence that it was for a queen. Evans, who had excavated the site in 1901, saw the room as a domestic space. From looking at the floor plan, the room seemed secluded from the rest of the palace. Because of the time period Evans lived in, he saw the room as a space for women to retire and withdraw from society. There is little to no evidence for either statement, but the name Queen’s Megaron stuck. (Evans 1901)

Nicholas Mayeux '24