Hugh Sackett is most famous for his archaeological excavations at Lefkandi and Palaikastro. His work has been called the “most significant of the archaeological projects conducted by the British after the Second World War” (Reyes 2020). But what actually happens during an archaeological excavation? It’s a lengthy process, but each step can be sorted into the following categories: Discovery of a Site, Mapping the Site, Excavating, Artifact Analysis & Interpretation, and Publication & Curation. The specifics differ from site to site, from permits needed to the number of artifacts found; but, in this exhibit, we’ll use slides from Sackett’s own collection to create an overview of how general archaeological work is completed.

Discovery of the Site

Archaeological sites can be discovered in many ways. One method is talking to the locals of the target area. Often, they’re already familiar with which sites have historical significance or have yielded artifacts in the past to those that own the land. Sometimes landowners seek out archaeologists when this happens, curious to know what else could be found in their own backyard.

Technology also plays a large role in discovering archaeological sites. Through various methods, such as aerial photography and satellite imagery, scientists can view an area of land from above, a much faster way to view more land than searching on the ground. One method, LiDAR, or Light Detection and Ranging, uses lasers to search the ground, allowing scientists to digitally map the land below them (Fagan & Durrani 2016). This is especially helpful in areas where the ground is not as visible, such as jungles or thick forests.

The biggest obstacles in discovering new archaeological sites are visibility and obtrusiveness (McManamon 1984). The visibility of a site refers to how it has been hidden over time by dirt, sand, vegetation, etc. Obtrusiveness, on the other hand, is how easy it will be to discover a site. The lower the level of obtrusiveness, the harder it tends to be to discover the archaeological remains.

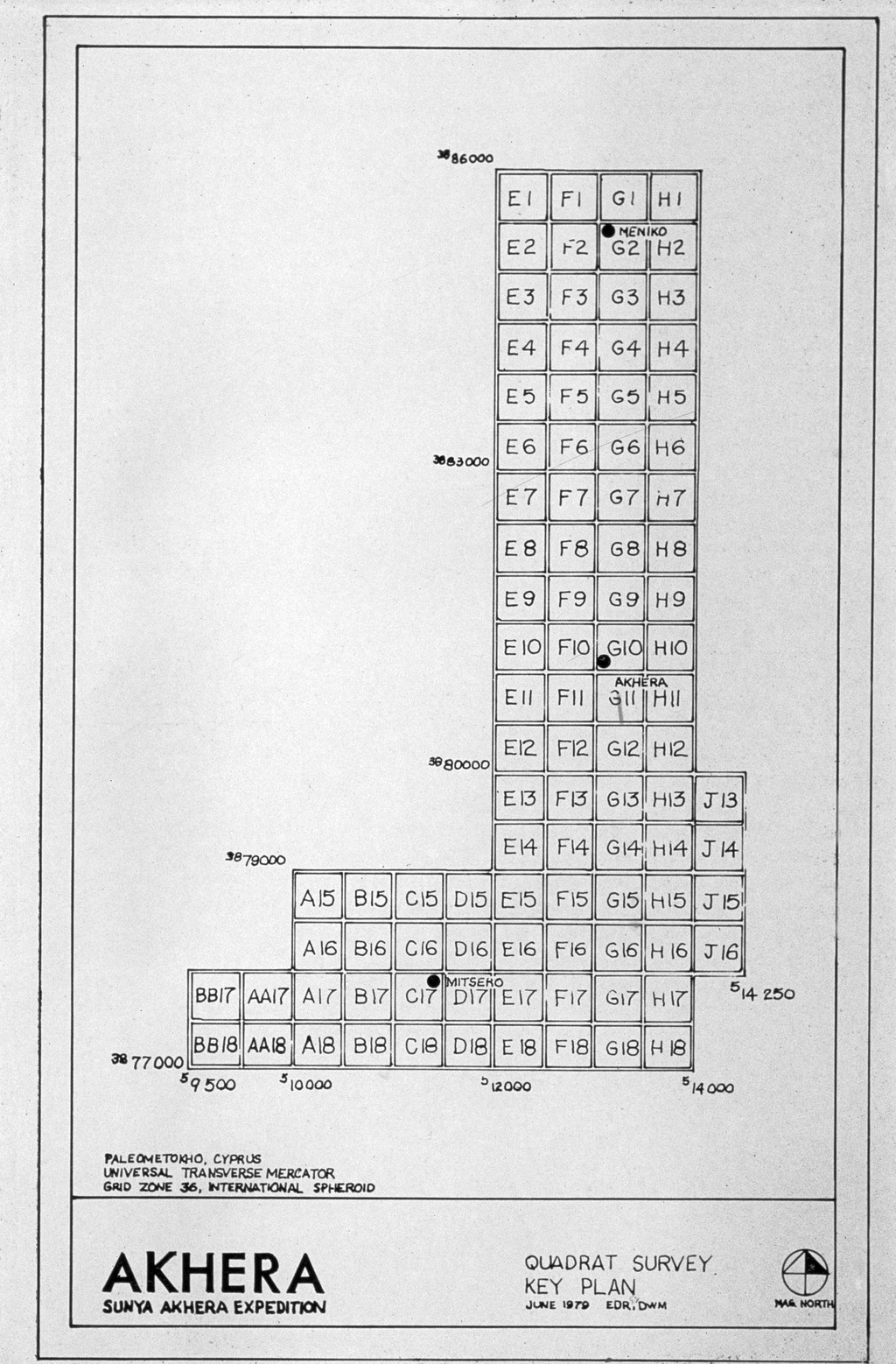

Survey grid of Akhera, Cyprus (Bryn Mawr 1982).

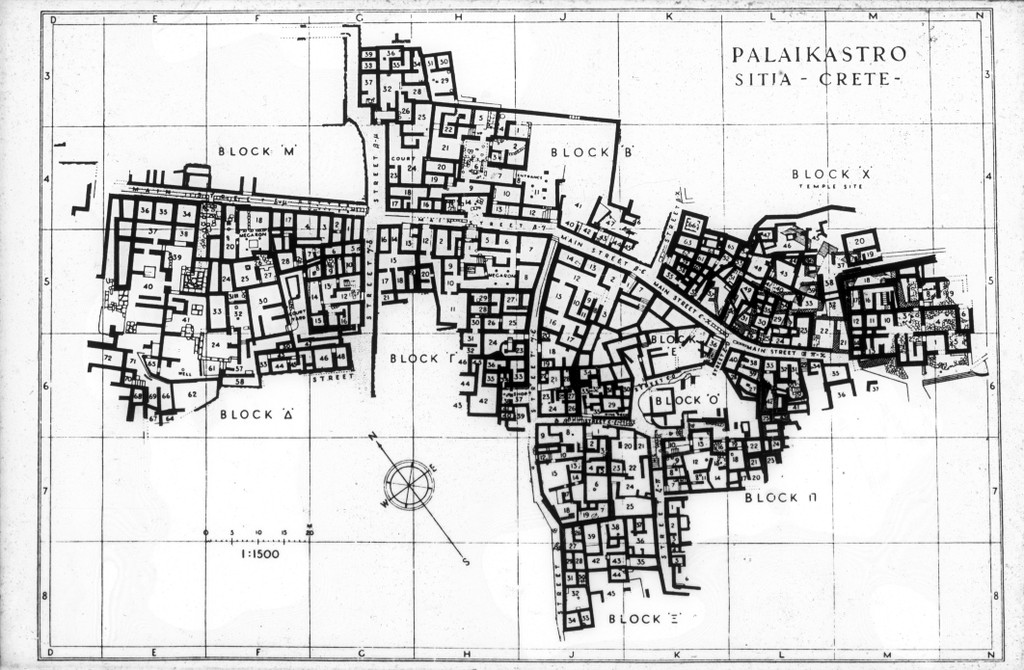

A site plan of Palaikastro, a coastal village on Crete, on a grid with 20 m. squares (Graham 1962).

Mapping of the Site

Once a site has been discovered, modern archaeologists are careful to plan their excavation before digging. This may seem like an obvious step, but many early archaeological sites were forever damaged due to rushed or careless excavating. In the mid 20th century, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Tessa Wheeler, and later Kathleen Kenyon, revolutionized the field of archaeology with the Wheeler-Kenyon method of excavation. It was first used at Verulamium, a Roman site in England, and refined at Jericho in Israel.

The Wheeler-Kenyon method uses a grid-system to organize the excavation process. The site is divided into 5-meter squares, leaving a grid of dirt that allows archaeologists to see the “strata” or layers of earth in each area of the site. This element of the method led to it also being called “controlled stratigraphic excavation” (Callaway 1979). Overall, the Wheeler-Kenyon method brought a new level of attention-to-detail and organization to archaeology.

The influence of the grid-system excavations can be seen in these plans. While they are not following the specifics of the Wheeler-Kenyon method, they provide evidence that other archaeologists built upon it with their own twists. For example, the Palaikastro plan (Peabody 1962) shows a large-scale grid-system, with the layout of the palace walls depicted and the grid imposed upon the blueprint with much larger squares. The Akhera plan (Peabody 1982), on the other hand, is a more geometric take on survey mapping. The site is shown as a series of squares, roughly in the shape of the remains being excavated.

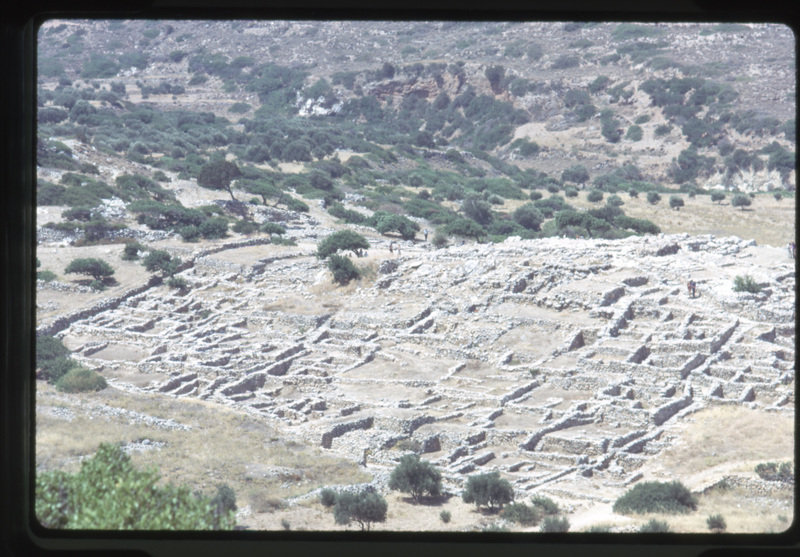

Excavation

After the planning stages, it’s time for excavation to begin! Each site is unique and therefore utilizes different techniques. This has led to many disagreements throughout archaeological history, leading archaeologists to create theoretical schools. At its core, though, each excavation involves uncovering a site, recovering artifacts and architecture, and recording everything.

Sackett's most well-known excavations were Lefkandi and Palaikastro. Both sites were excavated, at least in part, by the British School. (Cadogan 2020). Sackett taught during the school year and excavated every Summer, a common practice that continues in modern archaeology. Students had the opportunity to participate in real, groundbreaking excavations while gaining necessary experience.

Terracotta figurine of horse from Geometric Period (Peabody Museum)

Pottery cover of a pyxis - a small box, perhaps for medicine or jewelry - from Geometric Period (Peabody Museum)

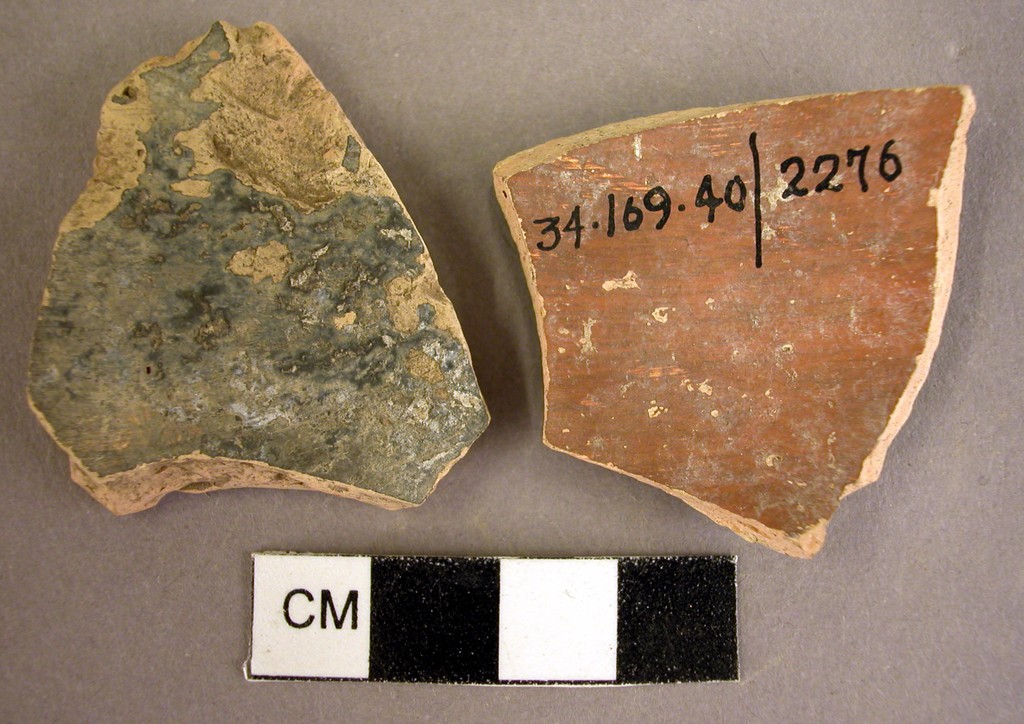

2 Mycenaean potsherds from the Helladic III period (Peabody Museum)

Artifacts: Analysis and Interpretation

During excavations, any artifacts that are discovered have to be handled carefully. Many materials are fragile, and have only become more so with age. As the field developed, artifact collection became more precise and organized, much like mapping and excavation. Using the grid system also allows archaeologists to concisely mark where in the site each artifact was found.

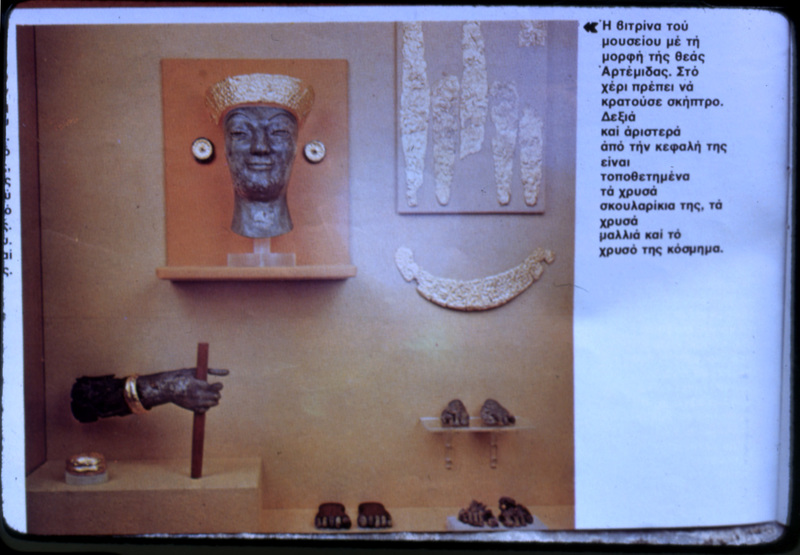

Once they’ve been collected, artifacts have to be analyzed and interpreted. Everything from potsherds to monumental sculpture has the potential to reveal something new about the site where it was found. New technologies are constantly being updated and invented such as radiocarbon dating, trace element analysis, and even DNA (Fagan & Durrani 2016).

Many archaeologists disagree on the interpretation aspect of artifact analysis. The lines of scientific evidence are much clearer than artistic, historical, or cultural interpretation. Some scholars feel that no assumptions should be made – only that which can be absolutely backed up with fact should be concluded. Others feel that not only is there room for conjecture; and in fact, that it can be useful to speculate what an artifact might say about its culture.

Publication and Curation

Another very important result of archaeological excavations is how the information learned during the process is shared afterwards. The two most common methods are publication and curation. The latter includes museum exhibits, permanent collections, and archives. The former covers a variety of media, from scholarly papers to lectures to documentaries, and more. Through both, the knowledge gained from archaeologists’ hard work can be shared with their coworkers and the public at large.

Brittany Ashley '23