Comprehension of life and values throughout different periods of ancient Greece are in a constant state of refinement. Both through efforts pertaining to archaeology and art history, new information is always being added to the field. Ancient Greek artwork can be especially valuable in ascertaining these aspects of various ancient Greek societies due to a multitude of factors, including Greek interest in art and intent behind the depiction of certain imagery. Hugh Sackett’s documentary photography of some vital artifacts, along with several additional sources, is among the work that can greatly aid in illuminating the complexities in ancient Greek relationships to the world around them, such as the tension between ideas of domination over and respect of the natural world.

Domination

Ultimately, many seminal instances of depictions of nature within ancient Greek artwork communicate a likely sense of superiority on the part of humans. For instance, among Sackett’s slides is an artistic depiction of what is likely Minoan bull-leaping- a mysterious ancient practice among the Minoan people, who occupied the island of Crete during the Bronze Age. A famous interpretation of the practice, as described by John G. Younger in an article regarding its depictions, consisted of “...a bull in flying gallop and an arched... leaper, whose head and hair are in contact with the bull’s head, and whose feet touch the animal’s back. The stumps of the arms are held close to the chest.” (Younger 1976, 126) While the specific purpose of bull-leaping to the Minoan people ultimately remains unknown, several theories pertain to it perhaps being a kind of coming-of-age ritual for adolescents. Regardless, the show of power and bravery on the part of the leaper, as well as the immense danger the bull posed to them indicates a great value placed on displays of control over such powerful beasts- in this sense, it can perhaps be compared to the more well-known practice of Spanish bullfighting.

Bull-Catching Scene Painted on Back of Crystal Plaque

section of a crystal plaque likely depicting bull-leaping, an artistic topic common to Minoan

artwork. These images depict human forms of indeterminate gender or sex performing acrobatic

leaps over the bodies of charging bulls. While the exact purpose of the ritual is unknown to

modern researchers, it seemed to be deeply important to ancient Minoan people

Chigi Vase

Found in modern-day Italy, the vase is notable for its intricately painted decorations. The

imagery, while identifiable to modern art historians and archaeologists, has never been

definitively linked together- many of the scenes appear disconnected from the others.

This proposed value is one seen in other time periods and subcultures of ancient Greece as well. This can be seen in artifacts like the Chigi Vase, a piece of Daedalic pottery from around 640 BCE. The vase is another somewhat mysterious piece of Greek art history, with special interest centering around its decoration. The vase, from bottom to top, depicts rabbit hunting, horse-riding, the myth of the Judgment of Paris, famous for being the event which kicked off the Trojan War, and a hoplite battle, a form of fighting which notably would have been outdated at the time of the vase’s creation. Despite being seemingly disjointed, some scholars have argued that connections can be drawn between all of the scenes. Among these scholars is Jeffrey M. Hurwit, who proposed that the vase’s decorations could all reference different stages in the life of a Corinthian man, possibly specifically centered around warfare (2002). Hunting and horse- riding both included the development of skills valuable to military efforts. Marriage such as that of Paris to Helen of Troy, would mark adulthood. Finally, warfare is actually depicted in the scene of hoplite battle. Within this context, Hurwit proposes, “[the] hunting, equestrian, and battle scenes... display the skill, courage, and elitism of the ideal Corinthian male” (Hurwit 2002, 16), making the vase an arguably idealized depiction of life and gendered expectations within Corinth at the time. The hunting and equestrian scenes are especially relevant to ideas of relationships to nature- both are among the more “grounded” scenes on the vase, both being skills many men would be likely to learn throughout their lives, and clearly represent further shows of power exertion over the natural world. The animals the boys in the hunting scenes pursue will be outright killed, while the horses the young men are riding are domesticated and are being utilized as tools.

Reciprocity

It is vital to note that a sense of authority over animals on the parts of humans does not necessarily preclude respect for inhuman beings, and by extension, the larger natural world. Within a 2010 article, Kristin Armstrong Oma notes that, often, relationships between animals and humans are based in “the notions of trust and reciprocity are at the core of the social contract”, (Oma 2010, 178) further elaborating through a description of a traditional Greek community, where relationships between domestic animals and owners are largely considered close. The animals are also considered vital to household economics, resulting in a dynamic based in reciprocal care and trust. To return to the Chigi Vase, an example of a similar dynamic can again be seen in the depiction of equestrianism. While the horses being depicted were indeed being used as tools, this did not mean necessarily they were not respected. Arguably, their very inclusion indicates their cultural value. Since the decoration of the vase would be intentionally chosen, there’d be no use in including unimportant elements of society. A further show of these concepts, again in the form of a horse, is an Iron Age figurine, depicting the animal in a simplified, shape-based style. At the time, horses were a great show of status, since they indicated both the state of being a warrior as well as the ability to farm- the use of iron, a metal that was deeply valued for toolmaking during this period to make a purely decorative figurine is indicative of these animals’ cultural value.

Another instance of a bull fresco from elsewhere in Minos is seen in The Bull Leaping Fresco at the Ramp House at Mycenae. As Maria C. Shaw describes in an article on the topic, multiple fragments depict bulls, with “No. 5 [showing] the belly and two lower legs of a bull trotting to the left” (Shaw 1996, 175), and “No. 6 [showing] another white bull, again with dapples and diagonal black lines indicating the hair...” (Shaw 1996, 175). The detail these animals were portrayed with supports the idea that artwork found at Knossos is indeed indicative of culture-wide interest in the bull. It seems that the physical prowess of the animal was greatly respected by the Minoans.

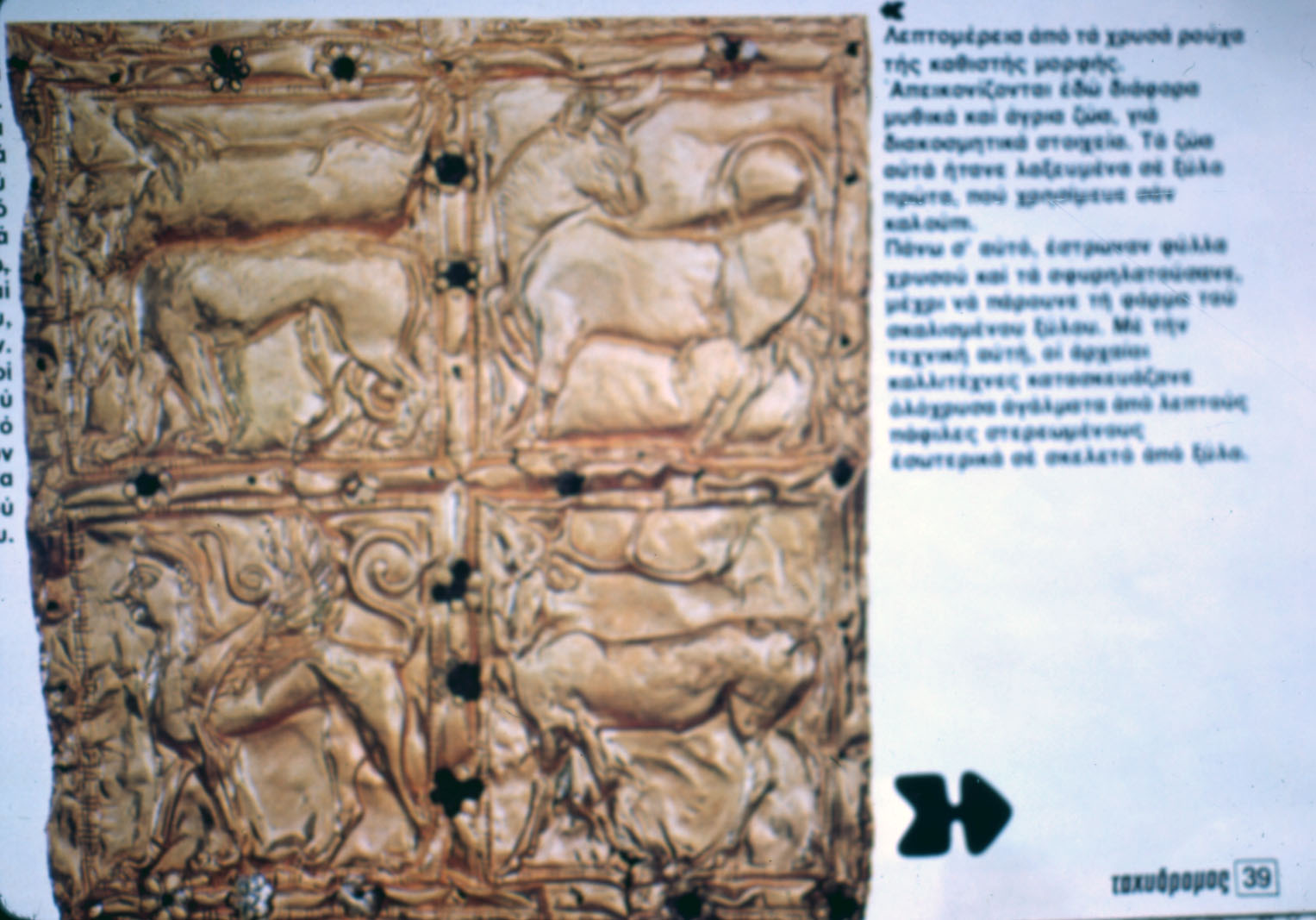

Furthermore, another of Sackett’s slides, shown below, is indicative of the way a respect for nature aided in stylistic development. The gold plaque, from 6th century Delphi, depicts four animals, which, regardless of mythological status, are rendered with notable detail in the animals’ bodies. The ways their skin folds, parts of the body taper, and the way their bodies are constructed to give the illusion of 3D space all show a great interest in the quality of naturalism, a kind of idealized depiction of the natural world which later became vital to Greek artwork. Just as the simplified form of the aforementioned Iron Age horse figurine displays an interest in simplifying the form, this plaque displays an interest in depicting a more “fleshed out” form, so to speak. As Jeremy Tanner discusses in a 2001 article, “...aesthetic languages vary in the degree to which they chose to, or are able to, exploit predispositions for sensory response... for culturally specific purposes”. (Tanner 2001, 260) Ultimately, by this, Tanner means that all stylistic choices serve specific cultural goals, making choices like a shift to naturalism more indicative of the values of wider Greek culture and their development over time than merely a desire to depict things “realistically.”