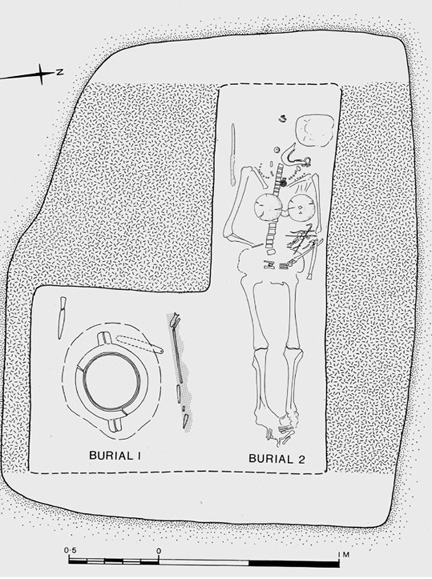

Lefkandi was not always known for its multitude of archeological treasures. However, the Island of Euroba, home to Lefkandi, has recently become increasingly important in the narrative of Ancient Greece. Today, one of the most impressive archeological discoveries from the island comes in the form of a burial site, The Lefkandi Toumba Complex, also referred to as the Toumba. The Toumba itself dates back to roughly 950 BCE and exists in a place of academic controversy. There is no clear answer to the functionality of this building, such as whether or not it would have served as a cult building or a cemetery (de Waele, 379). We do know, however, that there was only one burial site in the center of the Toumba consisting of one cremated man, an inhumed woman, likely his consort or human sacrifice, and four entire horses.

This burial (seen in Figure 1) stands out among the other gravesites at Lefkandi for multiple reasons: The individualized burial suggests the importance of the man buried here, meaning we could be looking at an aristocrat or warrior. Moreover, the ceremonial inclusion of items such as pottery, glass beads, gold, and ivory suggests that the man was not only important but that he was wealthy. However, the body of the man was cremated, thus not allowing any sort of physical adornment. The woman buried alongside him, however, was inhumed with a multitude of finery, namely, golden and ivory jewelry. For as long as bodies have been buried, we have seen the inclusions of individualizing markers, especially for those wanting to display wealth in the afterlife. Being laid to rest alongside one's wealth has been universally used as a status marker and ceremonial celebration. Still, it also indicates to modern audiences the care that went into these practices, as well as the importance placed upon Earthly goods. The jewelry and bodily adornments buried alongside the woman at The Lefkandi Toumba Complex help us understand the role of wealth and beauty in the ritualistic practices of death.

It is first pertinent to understand just how decorated the body of the woman at the Toumba was. Her body was placed parallel to that of the man and was buried alongside numerous pieces of golden and ivory jewelry (L.H. Sackett, 171). Included in her tomb were multiple types of necklaces, including an ivory necklace comprised of miniature figural sculptures, a completely golden chest plate, gold earrings, gold pendants, and gilt iron pins (L.H. Sackett, 173). One of our first insights into the life of the individuals buried here comes from the inclusion of the gold. Precious metals such as this would have been rare and hard to find and were normally imported from Egypt (Berry). These pieces are especially shocking since Lefkandi was particularly isolated from the rest of the Aegean, making trade and import of this nature even more scarce (T. Arrington, 6).

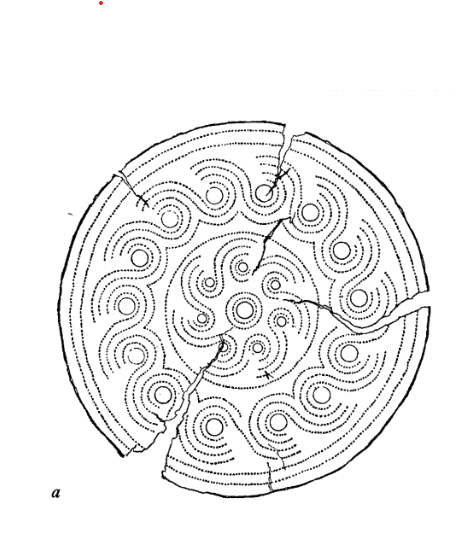

Further, detailed work, as was seen in the woman's golden adornments, would have taken a skilled craftsman to complete. The designs seen in her breastplate likely would have been cut from gold sheets and hammered for decoration. The pendants we see in the woman's burial site are similar in their crafted nature but likely would have been poured into molds (Berry). This signals to us that not only did the people of Lefkandi have access to precious materials such as gold, but they also had access to skilled labor, which would have been equally scarce during this period, which is well known as the “Dark Ages.”

Outside of gold, the Toumba at Lefkandi saw the inclusion of a necklace of ivory statuettes strung together. Closer inspection of the faience necklace offers us insight into the high status of the people buried in the Toumba: The piece is made of 53 individual figurative beads, most of which depict lion-headed figures, while the centerpiece (the largest among the others) shows the Egyptian Goddess Isis and her son, Horus (Hauser). Not only does this imply that these individuals were well-connected, but they were also wealthy enough to engage in cross-continental trade with Egypt. The most notable understanding of this necklace is that it would have been a Phonecian import, which is impressive because it means Lefkandi would have been included in a “trade network that went from Cyprus, Rhodes, the Aegean islands, Egypt, Sicily, Malta, Sardinia, central Italy, France, North Africa, Ibiza, Spain, and beyond even the Pillars of Hercules and the bounds of the Mediterranean.” (Negbi, 606). This means that, during a time when there was limited writing or monumental architecture, the individuals buried in the Toumba at Lefkandi, as well as the city as a whole, were still in contact with living traditions outside of Greece.

Jewelry can give us great insight into the lived experiences of individuals from the ancient world. Further, observing the objects included in a burial site allows us an understanding of what people and their communities valued during their time on Earth, as well as the goods and ideals they wanted to bring with them to death. In one breakdown of the objects included in the Toumba, as well as the surrounding gravesites located outside of the main building complex, scholar Nathan T. Arrington regards the inclusion of jewelry as “talismanic practice,” or rather, “trinkets,” as the author calls them, that are imbued with magical or spiritual properties (Arrington, 2). In this case, the inclusion of the jewelry shifts from an Earthly desire to be remembered as beautiful or wealthy into that of ecclesiastical forethought.

The wealth of jewelry and adornments presented in the overall Lefkandi Toumba Complex is unlike anything else seen during the Greek Dark Ages. The sheer number of impressive inclusions in the gravesites stands out as unique and allows modern audiences to understand the ancient emphasis put on beauty and wealth. Since there were no practices such as writing during this period, looking at the resources available helps archeologists and audiences create parallels to their own lives and formulate questions about the ways in which ancient societies prioritized things and if we, as modern viewers, have similar mannerisms. We are left with the question of how we prioritize beauty and wealth before and after death.

Kait Berry '25