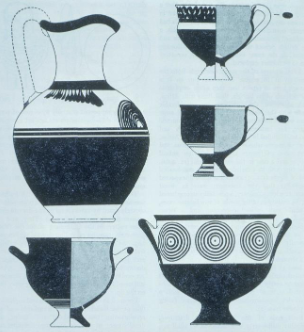

Lefkandi is an ancient coastal village and major Bronze Age and Early Iron Age archaeological site, located in the central-west part of Euboea, Greece. Archaeologist Hugh Sackett joined the Lefkandi excavations after the initial excavations from 1964 to 1966. When Sackett joined in 1968, the excavations would go on to include a vast burial ground to be discovered in a year's time at Lefkandi. Sackett continued to excavate at Lefkandi during the later periods of excavation in the 1980s to 1990s. The Lefkandi excavations brought forth a plethora of archaeological materials, including jewelry, metal tools, figurines, and detailed pottery vessels. Moreover, Lefkandi provided a vast insight into pottery from the Protogeometric period, a phase in Ancient Greek art ranging from 1025 to 900 BCE (i.e., the Iron Age). The Protogeometric period is known for its move toward purely abstract representations on pottery. Major features of this art period include compass work creating perfect geometric circles, other shapes (triangles, diamonds, etc.), no color variation, and solid black horizontal bands. Protogeometricn pottery was developed during a time of economic recovery from the dramatic fall of the Bronze Age in Ancient Greece; pottery production had just begun to ramp up again. Mass production of protogeometric pottery was facilitated by a pottery wheel faster than it previously was, allowing for more consistent and durable pottery vessels.

This exhibit offers a glimpse into this brief but memorable period in Ancient Greek art by analyzing the Protogeometric pottery found at Lefkandi by Sackett and other members of the excavation throughout the decades. The goal is to gain a deeper understanding of not only Protogeometric pottery itself, but also the important contribution Sackett made to the study of Protogeometric pottery. Furthermore, this exhibit explores why this pottery style continued to influence Greek pottery and art for centuries, culminating in the Geometric period (i.e., 900–700 BCE).

The Tombs: Protogeometric Styling in Death

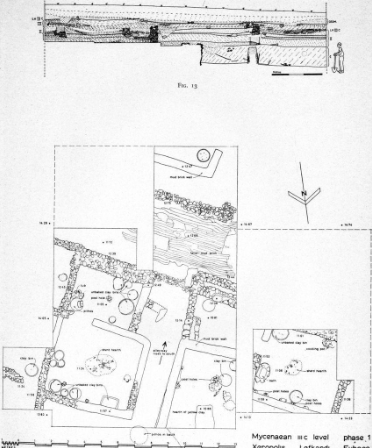

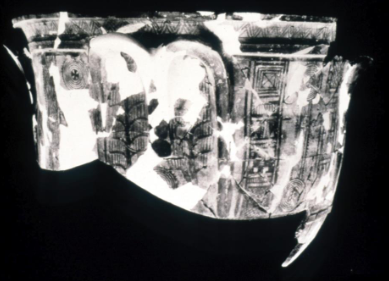

The tombs at Lefkandi were discovered by chance in 1969, in an area thought to be a settlement possibly dating to the Sub-Mycenaean and Protogeometric periods. Not long after the discovery, true identity of the area was confirmed as a massive burial ground. Sackett was largely involved in the Lefkandi tomb excavations throughout the 1970s to 1990s. In those years, a total of 83 tombs and 34 pyres were excavated; the findings were eventually published. Numerous archaeological materials found in these tombs range from weapons, dress fastenings, pottery, and many more. Originating from within Euboea and the wider Ancient Mediterranean, the objects display various types of economic statuses among the deceased. It is of no surprise that scholars are still shifting through these finds, trying to learn as much as they can about the people buried there. Moreover, it is also not shocking that a multitude of pottery has been found around burials and in tombs during the Lefkandi excavations. In the Ancient Greek world, people were often buried with kind of object, known as “grave goods” in archaeology. These grave goods provide a glimpse into the importance the Greeks placed on a peaceful transition into the afterlife. It was the deceased families’ responsibility to ensure this transition, often through funerary pottery. Once the Protogeometric period transitioned into the Geometric period, funerary pottery became even more popular. The Attic region, specifically, is famed for its large amphorae and kraters that would decorate graves across the Ancient Mediterranean. The tombs at Lefkandi have revealed the multiple roles pottery took on within funerary practices in the Iron Age, from housing cremations to simply being vessels to the afterlife for loved ones.

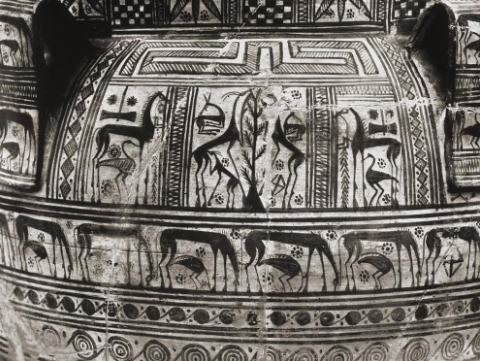

Sub-Protogeometric and the Turn Towards Picture:

The key features of the Protogeometric period lie in the use of shapes, as discussed. Nonetheless, the transition between the Protogeometric and Geometric periods (i.e., sub-Protogeometric) is marked by the use of pictorial art on pottery for the first time in the Greek world. The themes within pictorial art differed greatly depending on the region of Ancient Greece where the pottery was created. In Euboea, the location of Lefkandi, artistic motifs from the Eastern Mediterranean and horse imagery were preferred on pottery. The choice to take artistic guidance from the Eastern Mediterranean was not a common decision at the time; the only other area in Greece where these motifs were being used was Crete. The Eastern Mediterranean influence would have to wait centuries before becoming widely used in Greek art during the Daedalic Period (700–600 BCE). The most likely reason for the Eastern Mediterranean influence on sub-Protogeometric pottery in Euboea was the fact that the two regions had contact through trade, unlike most other parts of Greece at the time. These Eastern motifs are defined by the use of the Tree of Life and animals, both real and mythological, such as birds, sphinxes, lions, and griffins. The adoption of horses on Euboean pottery takes inspiration from the animals and landscape of Euboea itself. The scenes of horses range from those in the field to those in the stable, as Euboea had large areas of open pasture. Wealthy patrons who often commissioned pottery could display not only their ability to purchase personalized pottery but also horses, which were a symbol of vast wealth and power during this period. In short, Euboea exhibits great duality in its utilization of pictorial art on sub-Protogeometric pottery, portraying motifs from far away to familiar scenes of home.