The modern nation of Greece gained its independence as a nation for the first time in more than 2,000 years when it declared itself an independent nation from the Ottoman Empire, an event that “may be interpreted as the specifically ‘Greek exit’ from tradition - as an undoubtedly unique event of momentous importance” after gaining control of the southern part of the peninsula on March 25, 1822 (Lekas 2006). However, according to the White House Archives, full independence of the country wasn’t recognized by the Ottomans until 1830. In addition to cataloging sites and artifacts of times past uncovered from his archaeological excavations, archaeologist Hugh Sackett took quite a few pictures of modern Greece. Along with landscapes, flora, and other subsets of these pictures is shots of people in modern locations.

What is interesting about these photos of people is that many seem to intersect with the more recent history of the Greek revolution than most people today would likely expect, with discussion of the country being largely about its Classical period. As it turns out, most of Europe thought the same when leading up to Greece’s revolution. This is largely because of two factors: the typical Classical curriculum of students, and the otherness imposed on the Eastern world. For example, the philhellenes, or lovers of the Greeks, according to Miriam-Webster, of whom people who fought for the cause of Greek independence were given the title

“…often wanted to believe that a hereditary nobility of mind and feature persisted stubbornly among the Greeks in their polluted, Ottoman environment. In a country like England, there was a strong feeling that the condition of political independence itself would rekindle the ancient virtue” (Cunningham 1978).

Lord Byron is brought up in particular in the discussion of the philhellenes because of his uniquely exalted position in the cause of Greek independence. Harold Nicolson, a writer most active in the 1920’s, and one who was on the board of Governors of the BBC, wrote that “Lord Byron accomplished nothing at Missolonghi except his own suicide; but by that single act of heroism, he secured the liberation of Greece” (Cunningham 1978). This is almost certainly an exaggeration, but one that is also echoed by more contemporary sources, such as when Paul Joannides writes “the impact of his poems, even in the weak prose translations of Amedee Pichot, can hardly be overestimated…” (Joannides 1983).

Interestingly enough, back in his home country, in his own time, Byron’s backing for his campaign was rather poor, as the committee that Byron was a part of, the Greek Committee of London, was originally started with “One of the main considerations in their plans was to forestall attempts by other countries to exploit the Greek situation” (St Clair 2008). In total, though, despite attempting to fundraise, “The total sum of money collected by the Committee was only £11,241, far less than the monies collected by the Societies on the Continent and only slightly more than the sum sent for relief of Greek refugees by the British Quakers,” despite being made up of “numerous Members of Parliament, several lawyers including a former Lord Chancellor, two retired generals and other military men, a sprinkling of scholars, academics, and clergymen, the poets Byron, Moore, Rogers, and Campbell, and others whose names were familiar to the public for one reason or another” (St Clair 2008).

Although Byron’s role and his exploits were exaggerated by later generations, he was confirmed to have seen himself as fighting for “…the ordinary, anonymous peasants, caught up in the tragi-comedy of the war in western Greece, far removed from the bickerings of…” the Turkish and the Revolutionaries, and as such is seen as a hero by many modern Greeks, despite his lackluster reputation in his home country (Cunningham 1978). In the end though, Byron never seemed to have seen any real combat against the Turks before his motley crew of his ‘Byron Brigade’ had begun to crumble to infighting and mutiny, and the only thing “…which the Greeks wanted from them was their stores”. He died in April of 1824, after an epileptic fit and then falling ill, with about four or five doctors “vying with one another to apply more and more extreme bleeding,” until it killed him.

By this point, the only thing the Greeks actually saw value in Byron’s group was in their weaponry, and in 1826, Byron’s base of operations in Missolonghi was destroyed in battle, along with large chunk of the city. Later, according to the official tourism site of the city, walls were erected around the cemetery used to house those killed in the battle of Missolonghi. Since then, statuary monuments to Byron have been erected around Greece, including this cemetery, known as the Garden of Heroes, and a “statue was raised in the Zappeion,” in Athens, in 1881 (Cunningham).

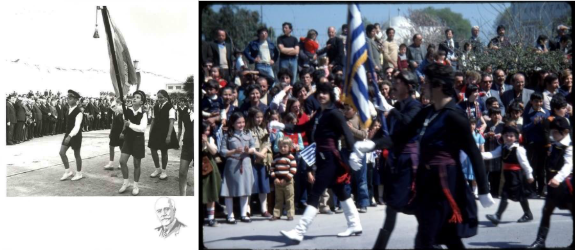

Traditionally up to today, according to the official European Commission’s site, parades of different sorts are very common occurrences to celebrate Greece’s Independence Day on March 25th, the official start day of the revolution, commonly either schoolchildren or military parades, with the largest being in Athens. Now today, after Greek independence celebrated its 200th anniversary and President Joesph Biden officially declaring the day to be “Greek Independence Day: A National Day of Celebration of Greek and American Democracy” in America, the country’s history is formed just as much by the people and events of the near as much as the ancient past.