Introduction

This collection of Roman coins, donated to Rhodes College by Auben Gray Burkhart upon his death in 2014, could not have been presented in this online exhibition without the practice of numismatics, or the study and collection of coins, in which he and his wife Tara avidly participated beginning in the mid-1990s. This page aims to outline how the coin market operates and how the Burkharts amassed their collection of coins that we have the privilege of accessing today.

Where are Roman Coins Found?

As with the majority of ancient art and artifacts, archaeologists often uncover Roman coins in controlled excavations across Europe, the Near East, and Northern Africa. They are then cataloged and entered into museum collections for preservation. However, for coins in particular, metal detectorists also frequently find Roman coins either on purpose or by accident. Recently, in December 2021, a metal detectorist discovered a hoard of 9,724 Roman coins dated to around 251 to 274 CE while searching a field in Cambridgeshire, England (Prickett 2021). In this case, the coins were taken in for conservation at the British Museum following their discovery, and they are up for acquisition by other museums in the area. However, coins found in this manner are not consistently submitted to museum collections, and some are instead acquired by private collectors who maintain the documentation of provenance in the event that the coin is resold to a museum, another private collector, or a coin trading company.

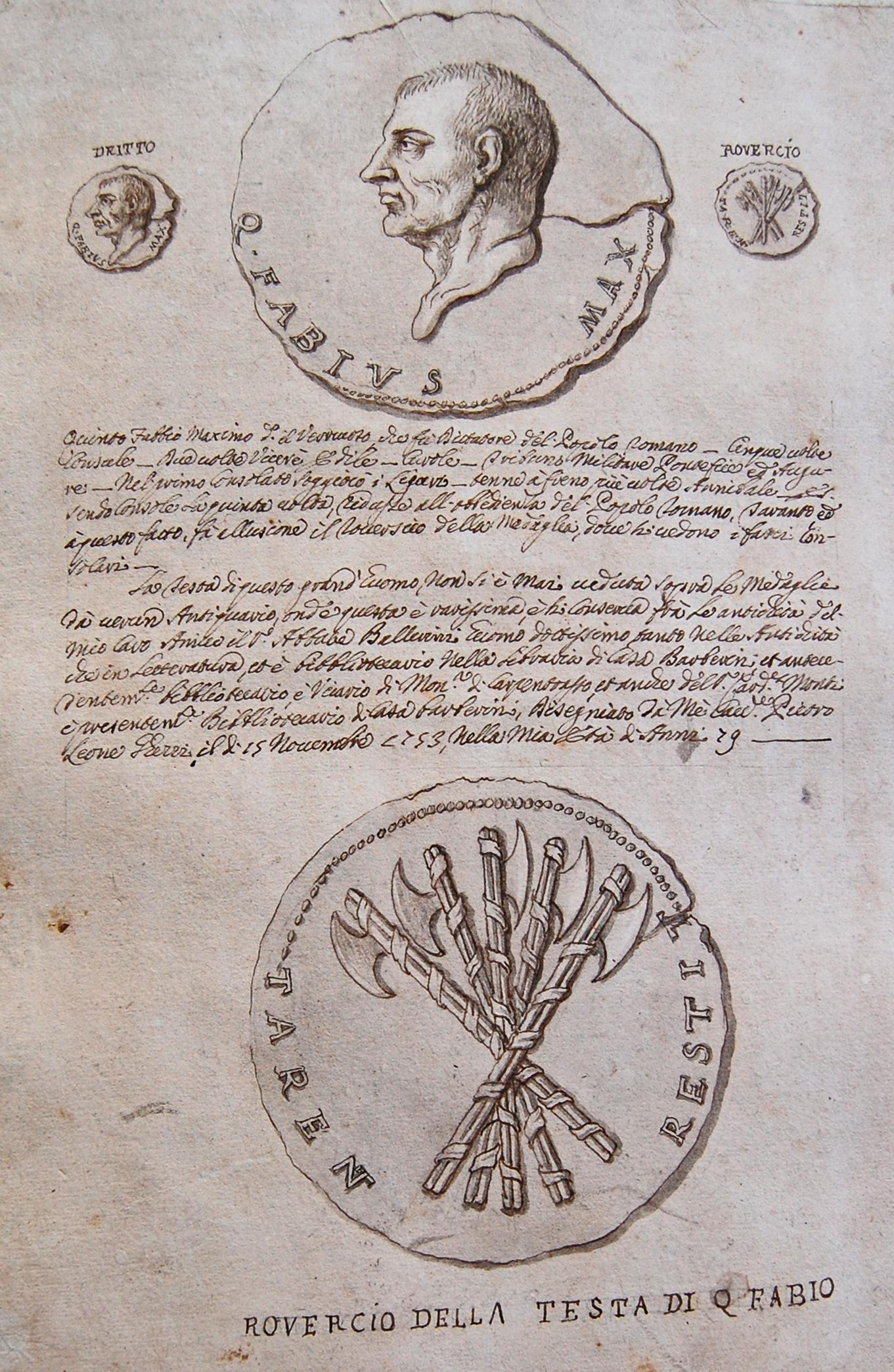

This ink and chalk drawing, created by collector Pier Leone Ghezzi in 1753, depicts the obverse and reverse sides of a Roman coin from the reign of Quintus Fabius Maximus. In the description, Ghezzi remarks that this is the first coin found with a portrait of Quintus Fabius Maximus, and he praises his fellow antiquarian, Abbot Ballerini, for this acquisition (The British Museum). This record of an antiquarian examining a piece from a private collection illustrates the importance of studying and preserving Roman coins even in the 18th century.

Who Sells Roman Coins?

In the Burkhart Collection, only two coin dealers who buy and sell Roman coins are mentioned by name: “Costal (Coastal?) Coins” and “Foothill Coins,” now known as Valley View Coins & Collectables in Santa Clarita, California. Although the metadata for the collection lists the name as “Costal,” this is most likely a misspelling of the Coastal Coin Company in Sarasota, Florida, one of the most reputable coin stores in the United States.

The majority of the Burkhart collection was bought in the 1990s and early 2000s, which coincided with the explosion of the Internet as a platform for commerce and the founding of ecommerce websites like Ebay and Amazon. Both Coastal Coin Company and Valley View Coins & Collectables currently reside within brick-and-mortar stores while also hosting online stores that ship ancient coins directly to the buyer. Although we might assume that any fully online store is unreliable, one of the foremost coin companies in the United States, Capstone Acquisitions based in Austin, Texas, conducts all ancient Roman coins sales on Ebay and Amazon while maintaining membership in credited numismatic societies like the Professional Numismatists Guild (PNG). As Roman coins become easier to access and purchase, more people around the world are able to build their own collections of ancient coins through these verified businesses.

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Obverse: The face of this coin, dated between 251 and 253 CE, has suffered from extreme corrosion, especially over the face of the emperor Volusianus. Burkhart purchased this coin from Valley View Coins & Collectables (formerly Foothill Coins), and its value was most likely impacted by its poor condition and bronze composition – a less expensive metal compared to silver and gold.

Reverse: In contrast to the front of the coin, the imagery on the reverse side is still relatively visible. Concordia, the Roman goddess of harmony, alludes to the peace and prosperity brought to the empire by Volusianus’s reign. The goddess is accompanied by an inscription that reads “CONCORDIA AVGG,” or “Concordia Augustus, as a reference to the former great emperor Augustus.

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Obverse: This denarius, dated circa 76 to 77 CE, is the earliest coin featured on this page, and it was probably purchased from the Coastal Coin Company according to the collection’s metadata. Its imagery is heavily worn and smoothed over but still visible. The obverse side features a portrait of Domitian as Caesar, although the coin was minted under the reign of Vespasian.

Reverse: The other side of the bronze coin is equally as worn, but the image of a pegasus with one front leg raised is visible. Because the Romans believed the pegasus to be an immortal creature, Vespasian most likely included it on the coin as an allusion to the lasting influence of his predecessor.

The slip, with “Domitian” labeling the emperor on the coin, also features the logo of the company from which Burkhart purchased the coin – most likely the Coastal Coin Company.

What Is a Roman Coin Worth?

Just as it was determined in the time of the Romans, the price of an ancient coin is primarily determined by the metal of which the coin is composed and how much that metal is worth at the time of purchase. The most expensive coins are those made of the most expensive metals, such as gold and silver, whereas coins made of less valuable metals like bronze and copper are typically less expensive to purchase. The Romans held what is known as a “metallist” perspective today, which takes into account the quality and quantity of precious metal within a coin to determine its worth (Scheidel 2010). The value of a Roman coin in the modern antiquities trade is entirely dependent upon the demand for that metal, which is in turn determined by the amount of that metal held in bank reserves, the value of the country’s currency, and inflation trends in that country. Therefore, the price of a Roman coin can fluctuate as the price for its metal fluctuates.

The obverse of this gold coin, dated to ca. 324-325 CE, depicts a profile portrait of the Emperor Constantine with the inscription “CONSTANTINUS PF AVG,” meaning “Constantine, Pius Felix Augustus.” This title is a testament to his power over the empire, as he is directly connecting himself to his predecessor Augustus. Choosing bright gold to compose the coin would also be a suggestion of his wealth and increase the value of the coin in both ancient and modern times.

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Image Credit to: Auben Gray Burkhart Collection, DLynx

Obverse: The front of this coin, composed entirely of gold, features a frontal portrait of Justinian I who ruled the Byzantine Empire following its separation from the Western Roman empire. Dated to around 535 to 568 CE, this coin does not fit into the timeframe established by the rest of the coins in this exhibition, but its pure gold is an example of a coin that would consistently be worth more than a bronze or silver coin.

Reverse: The back of the coin depicts an example of an early Christian image of an angel holding a cross. Justinian I, following his predecessor Constantine, adopted Christianity as one of the primary religions of the empire in contrast to the traditional pagan Roman religion that the rest of the Roman emperors adhered to and added to their coins.

Problems in the Coin Market and Antiquities Trade

Though the authenticity of the Auben Gray Burkhart collection of Roman coins is verified, forgeries are abundant in the antiquities trade today, especially as the market shifts away from in-person shops in favor of the ease of online sales and auctions. However, this problem is not limited to the modern coin market. Innovations throughout history from ancient times to the 19th century made reproducing counterfeit coins easier and therefore made them more prevalent in the coin market. One counterfeit coin artist active in the mid to late 1800s, identified as M. Sazonov, admits that he invented one method of producing more valuable ancient coins out of less valuable ancient coins. He explains that he would choose a common silver or copper Greek coin, knock off the existing designs on each side, and replace the imagery with that of a more expensive coin while preserving the coin’s original patina (Golenko 1975). This account is just one example of how counterfeiters are able to create replicas of ancient coins that are almost indistinguishable from the real versions.

Another issue plaguing the coin market is the trafficking of cultural property, in which authentic ancient art and artifacts are illegally exported from their countries of origin to be sold to foreign buyers. For example, in the case of a Roman coin excavated in Italy, the seller or the buyer must obtain a permit authorized by the Italian government that allows them to transport the coin outside of the country’s borders. In 1970, UNESCO held the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property to regulate the laws regarding the trade of art and artifacts and prevent criminal activity in antiquities markets. Coins are listed as cultural property under Article 1 of the notes from the Convention: “antiquities more than one hundred years old, such as inscriptions, coins and engraved seals” (UNESCO 1970). The United States distinguishes its own laws regarding the illicit trafficking of ancient coins, which allows the U.S. Customs and Border Protection to seize any package suspected to be carrying trafficked coins and places full responsibility on the importer to acquire the proper permits for international transportation (Tompa 2022). Even with these international and domestic laws in place, trafficking continues in the market today, and artifacts such as coins must be purchased from a verified seller with a documented record of the item’s provenance.

These terracotta molds from the city of Arsinoe (now Faiyum) in Egypt, created ca. 200-400 CE, are impressions taken of genuine Roman coins that could have possibly been reused to produce multiple counterfeits. Two molds feature images of the emperor Constantine, and all nine have obverse images of the god Jupiter that would have been accurate to genuine coins at the time, including coins in the Burkhart collection. Regardless of the original use for these molds, they serve as evidence that even ancient coinmakers had the means to reproduce coins on a commercial scale. Additionally, in 1988, archaeologists excavated a group of 800 clay molds from a wall in London dated to the second and third centuries CE that were used similarly to these Egyptian molds. They would have been used to cast copies of silver and copper-alloy Roman coins, including denarii, dupondii, and asses (Hall 2014). These two examples from the northernmost and southernmost points of Roman territory suggest that the illegal reproduction of ancient currency began in the Roman empire itself.

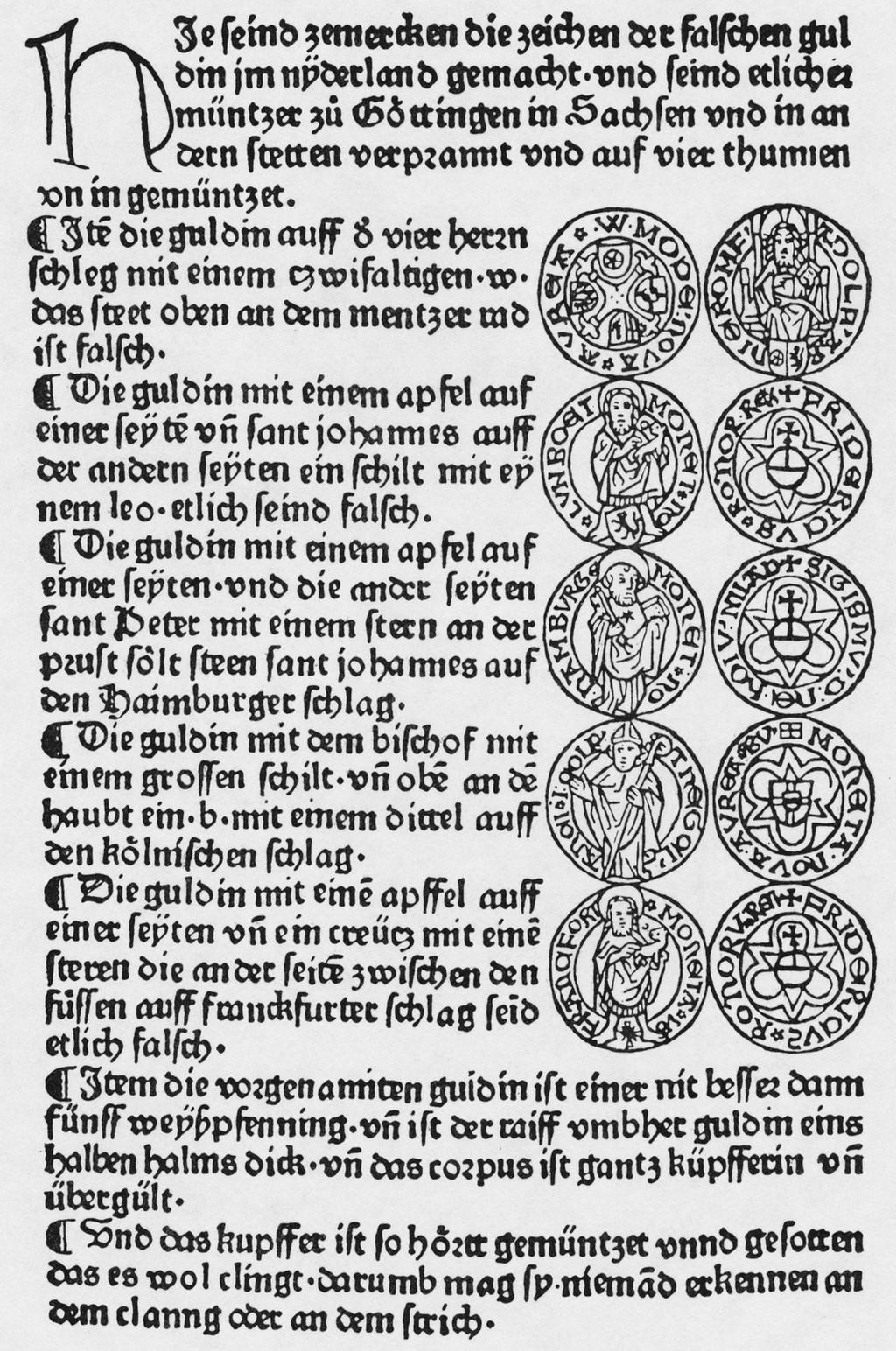

Again, the counterfeit coin problem has existed for centuries, as evidenced by this German manuscript from 1482. It documents ten different examples of medieval counterfeit coin faces with accompanying descriptions – meaning that people throughout history relied upon experts to verify the authenticity of their coins. These coins are not Roman, but their proximity in time to the Classical era compared to today proves that counterfeits have infiltrated the coin market since its beginning.

Page completed by Isabella Brewer, Rhodes College '24