Auben Gray Burkhart was a local Memphis attorney, philanthropist, and socialite. His wife, Tara Burkhart taught English classes here at Rhodes College for 20 years and was the Associate Dean of the British Studies Program. The couple were avid collectors, starting off with books, then British caricature cartoons, then stamps. They also traveled regularly, exploring the world and spending much of they time abroad in the United Kingdom to help with Tara Burkhart's research. Finally, in the mid-1990's, the Burkharts developed an interest in collecting coins. Auben Gray Burkhart began working with coin dealers and a friend of his who already had a coin collection. He made a list of emperors by year so he could organize the coins he bought, although he eventually grew his interest past Roman coins and bought some later European coins as well. Despite the size of the collection, collecting coins was a relatively short term hobby for Auben Gray Burkhart and the interest only lasted two to three years according to Bill Short, who was close friends with the Bukrharts and is in charge of the Rhodes archive collection at the Barrett Library. Mr. Short also remarked that the couple were "classy people, with a great deal of whit" and that they were "caring and wanted the best for their friends, family, and students."

As they began to age, the Burkharts started auctioning off many of their collections or donated them to various local colleges. Auben Gray Burkhart named Rhodes College as the recipient of the collection in his will and the college obtained it in 2014 after his death that year. Once Rhodes received the collection, Dr. Miriam Clinton, an art history and archaeology professor here at Rhodes, immediately started integrating it into classes. Each Roman Art and Architecture class from 2015 onward contributed to the preservation and documentation of the collection. The first class to work with these coins helped to clean them and learned basic art conservation. Another logged the information into an extensive spreadsheet and archive website, which included (but was not limited to) the dimensions, the date, the metal used, and the chemical analysis of all 117 coins in the collection.

Today, the physical collection remains in the Rhodes Archives in order to preserve them. Students are free to request permission to see them, but there is currently no dedicated viewing section in the library. The inability to physically showcase the coins is what led to the creation of this webpage, which allows a more accessible option to learn about this amazing gift to Rhodes College.

Special thanks to Bill Short, who was gracious enough to offer his time for an interview on Auben Gray Burkhart and who helped this class access and learn about the coin collection.

This coin, dated in between 222 and 234 CE, shows a bust of Severus Alexander on the front and a depiction of the Libertas on the back. Severus Alexander was known for being the second youngest emperor in the Roman Empire, starting his reign when he was only 13 years old. He mostly served as a figurehead in government and did not really have any power, but coins were still minted in such a fashion that they suggested he was a true ruler. On this coin, Severus Alexander is crowned with a laurel wreath to signify and solidify his status as ruler. On the back, Libertas holds piles in her right hand and a cornucopia in the other. Cornucopias were symbols of prosperity, so depicting Libertas with a cornucopia denoted that Severus Alexander brought prosperity and freedom to Rome.

Libertas was not only used in coin imagery by Severus Alexander. This coin from the Wriston Art Center Galleries at Lawrence University dates to 69 CE and also shows Libertas holding a cornucopia in her hands (as well as a scepter). Roman emperors constantly reused imagery like this as small pieces of propaganda.

Following the assassination of Severus Alexander and his mother by Roman soldiers, Roman senators chose Maximinus Thrax to rule the Roman Empire. Thrax reigned from 235-238 CE and was known as the first of the soldier emperors. Surprisingly, he was not born into the senatorial class, but was rumored to have come from a family of peasants. The name "Thrax" refers to his roots as a Thracian. His reign was short-lived because his soldiers assassinated him and his son in 238 CE. This silver denarius shows him facing to the right on the front. Like the image of Severus Alexander, Maximinus Thrax is also shown wearing a laurel wreath. The reverse shows the deity Providentia holding a wand over a globe and a cornucopia in her right hand, suggesting that Maximinus Thrax brought wealth and prosperity to the empire.

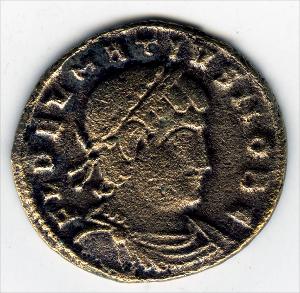

Delmatius (or Dalmatius) was one of Constantine I's two nephews. In 335 CE, Constantine I made him Caesar, a lower level emperor in the Late Roman Empire. This silver Delmatius coin dates in between 335 and 337 CE. The front shows Delmatius facing to the right, wearing some sort of crown. The back of the coin depicts two Roman soldiers holding a banner that says, "GLORIA EXERCITVS" which translates from Latin to "Glory to the Army,"a phrase that highlighted his military prowess as opposed to peace and prosperity. Shortly after Constantine's death, Delmatius was assassinated by Constantine's two sons, who wanted their father's power for themselves.

Justinian was most well-known for reclaiming much of the Roman Empire's lost territory and for building the Hagia Sophia. Although this coin is technically from Byzantium and not what we think of as the Roman Empire, it is still Roman in nature. For example, many Roman coins showed a ruler on the front and a winged victory or god on the back. Since Justinian was a Christian ruler, he took this trope and Christianized it, transforming the winged victory into an angel and holding a cross instead of a sword. The cross symbolizes that his power as emperor comes from God, which reflects the trope of divine right often found in Roman coins. By associating themselves with gods, Roman emperors effectively spread a message that their rule was willed by the gods and therefore they deserve to have the throne.

Constantine was one such emperor that implemented images of Victory as propaganda. For example, the image above, taken from the Arch of Constantine shows Victory with a war prisoner. This inclusion of Victory in the arch is meant to once again convey the message that the emperor is in power because the gods are on his side. The fact that Victory is actively watching over the prisoner only heightens this message.

Augustus famously used his supposed connection to gods such as Apollo in a similar way. For example, on the Ara Pacis (a building Augustus commissioned in Rome to celebrate his rule), he included depictions of swans at the bottom of the register. Swans were one of Apollo's sacred animals and their inclusion in the Ara Pacis refers back to Augustus implying that Apollo allegedly helped Augustus win the Battle of Actium and was allegedly Augustus' real father. In front of the Ara Pacis stood an obelisk, which was built in such a way that its shadow would directly line up with the Ara Pacis on Apollo's birthday.

Nero was part of the esteemed Julio-Claudian dynasty, a family descended from Augustus and (arguably) Julius Caesar. Despite his glittering lineage and the strong start to his reign, Nero began acting on darker impulses, which eventually grew to the point where he murdered his mother, Agrippina. As the Roman public turned against him, Nero grew more and more paranoid that someone was going to kill him, so he started killing anyone he was suspicious of, including his tutor Seneca. Eventually the Roman Senate declared him a public enemy and Nero fled to the country to kill himself.

This mostly copper tetradrachm was produced during Nero's reign sometime in between 54-68 CE. Although its features are heavily worn down, Nero's bust on the front is still visible. He is wearing a pointed crown as opposed to laurel leaves and is pictured facing to the right. Although there was text around the diameter of the coin, it has been worn down to the point where it's no longer legible. The reverse side of the coin shows Apollo Pythias, which links Nero back to Augustus's reign. Since the two were related, the connection to Apollo that Augustus started carried over to Nero.

While the Auben Gray Burkhart Collection is mostly made up of Roman Coins, there are a few from a more modern Europe. This coin was produced in 1689 CE and displays William and Mary, who were the British King and Queen at the time. The front of the coin shows overlapping busts of William (foremost bust) and Mary (the furthest bust) with the inscription "GVLIELMVS ET MARIA D G." The back of the coin shows a crown over the number four, indicating that it is a fourpence coin, along with the inscription "MAG BR FR ET HIB REX ET REGINA."

This coin closely follows many other Roman coins, especially on the front of the coin. While the appearance of two figures was uncommon, it was not unheard of.

This coin, taken from ArtSTOR's Slide Gallery, shows Nero and his wife, Octavia. Octavia was the daughter of Emperor Claudius, who was also Nero's stepfather. Octavia had an arranged marriage to Nero that took place when she was only 12 years old. Although she was popular among the Roman people for her virtue and reserved demeanor, when she was 22, Nero exiled her and then executed her.

This coin is meant to show the Roman public that the couple was united, especially because Nero's association with Octavia was a positive for his reputation. Stability as a couple might have been seen as a sign that the empire was stable as well. William and Mary might have had similar thoughts, as the composition of the front side of the coin shows a solid precedent to the William and Mary coin above.

Page Completed by Avery Comish, Rhodes College '24