From the earliest use of true coinage in the Roman Empire around 300 B.C. gods and goddesses have been used to exhibit the growing presence of the Roman Empire to the rest of Italy. Gods were symbols of various aspects of Roman culture and power, and generally it was the nobles who were tasked with keeping them content. However, under the emperor’s control, religion and coinage began to come together to emphasis their authority and influence on society. Shotter writes, “State religion was one of the “weapons” at the new government’s disposal.” While it was common to see the Olympic gods depicted in coinage, it is the use of minor deities that send different and more direct messages to whoever handles their coins. Unlike the major gods, the minor deities’ roles were more specific and less all encompassing. Though, their roles may not be as prevalent to society as the major gods, nevertheless, they were still regarded as higher beings to the Roman people and served as important icons to the emperor’s propaganda tactics. It is estimated that around only 20-30 percent of males and 10 percent of females were literate. Outside of the urban areas in western parts of the Roman Empire it was estimated that only around 5-10 percent of adult males were literate. Though this may not have been an intentional move on the emperor’s part, it was a a strategic one to use iconography of various minor deities to send non-lexical messages across the empire, and wherever the coins travelled. Even though they were not the main gods worshipped in day-to-day life, they were still well-known figures that regardless of your educational background, you would still be able to recognize. Often, the message associated with the deity was often unchanged, which allowed for less misconstruction among individuals and the message the emperor was sending.

Victory

Marcus Aurelius Carinus and his brother Numerian were elevated to the rank of Caesar in 282 AD. When Carus and Numerian left to campaign, Carinus was left in Rome to manage the government in 283. He was made consul and later after his father’s conquest of Mesopotamia Carinus was raised to the rank of Augustus. It was said that Carinus was the preferred ruler of heir of Carus because he maintained a “ruthlessness and military” that Numerian did not. After Numerian died, his army named a new emperor of the east, Diocletian. As Carinus campaigned against the Germans and Britons, another individual was challenging his power, Marcus Aurelius Julianus, the governor of Venetia. In 285 AD Carinus defeated Julianus, freeing him up to deal with Diocletian, but was assassinated by one of his own officers.

From Carinus’ history there are multiple conclusions on why the goddess Victory was in use of the reverse side of his coin. Carinus could’ve issued the coin with Jupiter handing Victory to himself in efforts to encourage a connection between himself and the divinities. Another interpretation could include Carinus wanting to be associated with his father’s image and victory against the Mesopotamians, and a symbolic representation of Carus passing the empire to Carinus. Finally, the choice of depicting Victory could be seen as Carinus trying to preserve his public image. Carinus’s reputation was said to be among the worse of the rulers. He amassed a list of nine wives, some of which he divorced while they were still pregnant and was known for having affairs with the wives of noblemen. Essentially, he was using the image of Victory to distract from his personal life and bring people’s attention back to his militaristic conquests.

Theodosius born in northwest Spain, learned his military lessons from his father who was a talented military commander by campaigning with their staff throughout Britain. After rising through the ranks of the Roman Army, he was crowned emperor of the East in 379 AD where he continued his battle against German tribes in the North. He eventually worked out an arrangement with the Germans, that in exchange of land provisions, their soldiers would the Roman banner when needed. However, to pay for this extended army Theodosius raised taxes heavily, decreeing, “No man shall possess any property that is exempt from taxation.” Throughout the rest of Theodosius’ reign, he was consistently at odds with either foreign opponents or facing backlash from the Roman people. After converting to Christianity, he began persecuting Arians and Manichaeans until they were driven underground. His choice of depicting Victory carrying a trophy while dragging a captive is meant to be used as a tactic to elicit fear throughout the empire. Victory dragging the captive emphasizes his ruthlessness when it comes to achieving power. In 394 he was able to unite the East and West one last time by defeating the West before he died a few months afterwards.

Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which legalized Christianity and allowed people the freedom to worship throughout the empire. This was a major turning point in the Roman empire because before the edict Christianity was not fully accepted in Rome. In 330, the same year Coin 85 is dated to, Constantine founded the port city of Constantinople which was the first city Christianity was designated as the capital religion. Though not explicitly stated, Victory on the prow of the ship is supposed to be symbolic of Constantine’s founding of Constantinople. Victory holding the scepter publicizes Constantine’s authority. When the average Roman views the count they will be reminded of Constantine founding of his new Christian empire. Victory in this manner is not necessarily being used as motif for the victory of war, but rather the victory of Christianity.

Pax

Pax

Victorinus along with Postumus were serving as consul, the oldest and most important magistracy. Consulship was voted upon by the Comitia centuria which was comprised of the richest individuals in Rome. Consuls’ duties consisted of exercising juridical power and commanding the Roman army. Following Postumus' death in 269 CE Victorinus became emperor after Marius could not establish his rule in the Gallic Empire. During the distress of the empire, Victorinus most likely decided to depict Pax on the reverse side of the coin to send the message of peace across the empire to soothe them. Viewing Victorinus on one side and Pax on the other forced the average Roman to associate the two together, making it easier for the Romans to trust that he will ensure peace for them.

Carausius of Antonius was a military commander for the Roman Empire during the 3rd century. In 286 AD he rebelled against the central Roman empire during Diocletian’s reign. He declared himself emperor in northern Gaul and Britain. Barker writes of Carausius, “Carausius stuck an enormous number of coins, of different varieties and types, which often carried official propaganda about his rule.” In some respects, Carausius may have been trying to invoke the history of the Pax Romana by issuing Pax on the other side for this specific coin. Usurping to power like he did most likely caused an uproar throughout his claimed empire. In efforts to appease the people it was a strategic move on his part to depict the goddess Pax. This symbolizes to the people that he in a sense is looking out for their best interest by trying to bring a newfound peace.

Genius

Diocletian was born to a poor family in Dalmatia around 245 CE. After joining the military, he rose through the ranks and served as commander of the imperial bodyguard in 283 CE. In 285 at Margum, Carinus’ army surrendered, accepting Diocletian as emperor, after one of Diocletian’s officers assassinated Carinus. Following this, Diocletian was kept busy with rebellions and fighting off invaders. However, through all this Diocletian made a huge step in Roman history by founding the Tetrarchy. This new way of government allowed for fours emperors that would rule the empire under four different capitals. Between 304 and 305 Diocletian suffered from an illness, which led him to relinquish the throne before his death in 311.

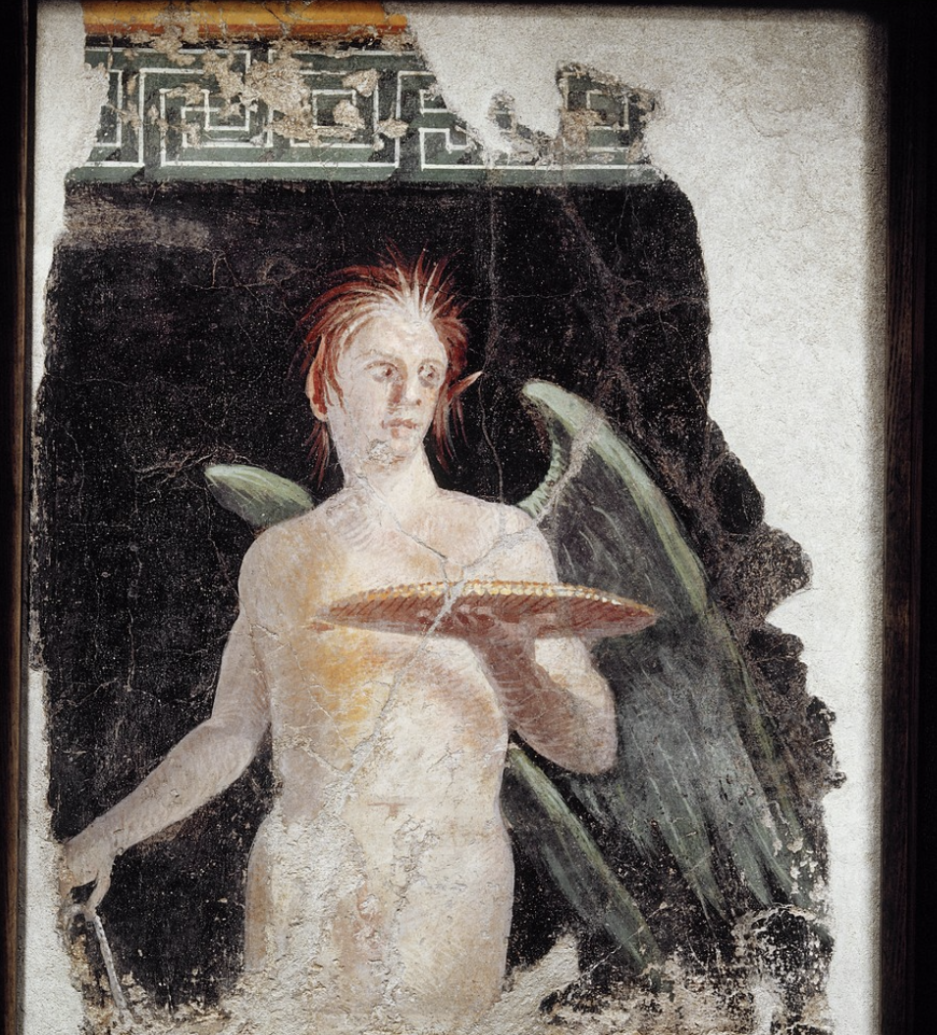

On the reverse side of Diocletian’s coin, the deity Genius is depicted. Genius was said to be a protecting spirit that stayed with man throughout his life. In the time of Diocletian’s sickness, Genius was depicted to invoke Diocletian’s Genius so that he would guide him into recovery.

Galerius was emperor of Rome from 305-311. He was appointed by Diocletian as second in command of the Eastern Empire. However, unlike Diocletian, Galerius was not favored as highly. In addition to raising taxes on the urban population of Rome, he also continually persecuted the Christians throughout his reign. In 311, Galerius came down with a lingering disease. Ancient historian Lactantius wrote of the disease that, “God struck him with an incurable disease. Ancient historian Lactantius wrote of the disease that, “God struck him with an incurable disease. A malignant ulcer formed itself in the secret parts and spread by degree. The physicians attempted to eradicate it… But the sore, after having been skimmed over, broke again.” Most likely following in the footsteps of Diocletian, once again the deity Genius was depicted on the reverse side of his coin. To the people, depicting Genius served as a humanizing factor between the emperor and the average Roman. Given that every man was said it have a Genius, most likely when they viewed the coin it inflicted a sense of remorse and compassion towards the emperor in his final time.

Page Completed by Nicholas Dillon, Rhodes College '24