Aurelian in Third Century Rome

Throughout the third century, the Roman Empire reaches from present-day Spain, through Northern Africa, across Asia Minor, and touches the edge of Saudi Arabia. The religious life of third-century was compiled of cults and their interactions with other cults. There was an emphasis on individuality and personal practices of piety.

The once-united Roman Empire split into three territories after the assassination of emperor Alexander Severus by his own military troops. The split of the Roman empire was preceded by a series of Civil wars in which Gaul, Spain, and Britain formed the Gallic Empire with their own ruler, while the eastern provinces formed the Palmyrene Empire. Successive emperors would have four-month to three-year rules; the turnover is a consequence of imperial dependence on the military of the army for support. Many were assassinated in battle or by their own troops because a new emperor would promise a raise in pay. Under the Severan Empire that preceded the string of short imperial rules, emperors had devalued the currency to afford pay raises for troops, which sent the empire into an economic downturn.

As Rome struggled internally, foreign powers attacked Roman borders. German, Gothic, and barbarian tribes threatened Roman defenses. A plague also depopulated the Roman Empire, from which the population would not recover. This period of crisis ended with emperor Aurelian who commanded the military troops to drive out the Gothic armies out of Roman territory and reunited the Palmyrene, Gallic, and Roman empires to become one again.

Though Aurelian was assassinated in his five-year rule, his coins ushered in a new era in Roman history with emergences of more personal religions. The reunited empire needed a new deity to unite them: Sol. The cult of Sol worship continued throughout the succession of Roman rulers.

Coin 023 Obverse

The obverse of this coin shows a bust of Aurelian from around 271 CE. This text is legible: IMP C AURELIANVS AVG, which translates to “Emperor Caesar Aurelian Augustus.” The titles "Caesar" and "Augustus" reinforce the divine power of emperors.

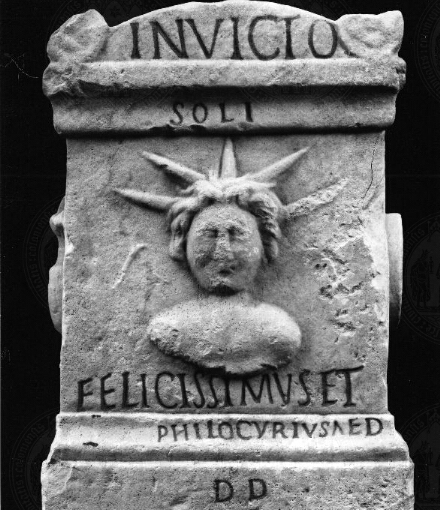

As pictured in the below relief of Sol, the god is depicted with rays of sun radiating from his head. Aurelian’s crown is also pointed in the same way, which draws a direct link between Sol and Aurelian to reinforce that they are connected. Both the text and the imagery point are proving that Aurelian is in fact powerful and divine.

Coin 023 Reverse

The reverse of this coin shows a woman on the left presenting a victory wreath to Aurelian, who stands with a spear. The text surrounding the figures spells RESTITUT ORBITUS “Restorer of the World.” Aurelian is standing in contrapposto in the same pose as Augustus of Primaporta, which is pictured below. Aurelian is directly linking himself to Augustus, who joined the Roman pantheon. Aurelian is combining his new legacy of divinity with the original deified ruler Augustus.

Album B with photographs of architecture, sculptures and decorative arts from Central and Lower Italy collected by Prof. Hermann Herdtle, Europeana

The Link to Augustus

Most Romans would have been very familiar with this sculpture of Augustus of Primaporta. In antiquity, Augustus would have been holding a spear. By posing like this statue, Aurelian is drawing a direct association to Augustus. It would have been a political advantage for Aurelian to establish a link with Augustus because of his divinity and role as head of Roman religion because Aurelian was placing Sol within the pantheon. Aurelian also would have continued the great military legacy of Augustus, who annexed Egypt, built roads to connect Rome, and assembled the Praetorian Guard to defend the empire. As a soldier-emperor, Aurelian would have wanted to prove his military leadership and skill. The prestige of Augustus would elevate Aurelian to a godlike status.

The Rise of Sol

Emperor Aurelian was awarded the title Resitutor Orbis, which means “Restorer of the World” for his reunification of the Roman Empire. Under Aeurelian’s command, the Roman troops took control over the Palmyrene and Gallic Empires and placed them under one ruler. In 271 CE at the start of his rule, Aurelian defended the Roman border against barbarian forces from the north and the south. For defense against other future invasions, Aurelian erected walls that would fortify the city. Other military achievements included retaking control over Egypt and defeating the Gallic tribes.

Once the Roman Emperor was re-formed, Aurelian distributed free food to citizens and reformed the coinage system by minting coins with a higher percent of precious metals. On the new coins produced in this period, Aurelian printed imagery of a new deity: Sol Invictus, meaning “Invincible Sun.” Sol’s purpose was to protect soldiers, and Aurelian elevated him to the status of the official deity of the Roman empire. Cult worship of Sol allowed Aurelian to gain political favors by elevating Roman elites to positions of power in worship.

Aurelian called himself dominus et deus, which translates to “master and god.” His divinity is traced back to his birth, which deified him during his lifetime and reign, while it was customary for an emperor’s successor to deify the previous emperor. Sol, then became a “divine sponsor” to Aurelian, which legitimized his reign.

Coin 022 Obverse

This coin shows a bust of emperor Aurelian from 271 CE, most likely when Aurelian began a program of reminting coins to connect him to the deity Sol. The Historia Augusta describes Aurelian as a “comely man,” with “severity and discipline” (Historia, 6.1). The bust on the coin depicts Aurelian as regal and authoritative with armor to show his military power and status as a soldier-emperor. This combined with Sol, patron diety of soldiers, cements Aurelian’s divinity because if Sol is a patron of soldiers, and Aurelian is a soldier, Sol is the patron diety of Aurelian as well.

Coin 022 Reverse

Though the image is worn and abraded, this image is a depiction of Sol standing with his right hand raised and left hand holding a globus or globe. There is a logical temptation to associate this globe with the earth as propaganda to prove that Rome could conquer the world. Instead, Sol is holding the globus of the Cosmos, or the entire universe, which represents his ultimate authority over everything. As seen in the image below, Emperor Constantine also used the imagery of Sol in his arch because the myth states that Sol presented the universe globus to Contantine.

The Future of Religion in Rome

Aurelian's cult of Sol united the empire under one emperor and one god, which paved the way for monotheistic worship. Emperor Constantine in 313 CE promoted religious toleration in Rome, leading to the rise of Christianity. A legend tells the story of Constantine receiving in battle a divine vision of the Chi-Rho sign, which was later associated with Christianity. At the time, the symbol was associated with Sol Invictus. Chi is the Latin letter K, and the Rho is the Latin letter R, which could stand for "KRonos" instead of the first letters of "Christ." The Roman diety Sol has similar ties to the classical god Kronos, who was the all-powerful god over time.

The deity that defended the Roman Empire very well could have been an adaptation of Sol. After Constantine's deathbed conversion to Christianity, the pagan cults eventually transitioned into Early Christian religious groups.

Coin 046 Obverse

This coin dates to 324-325 CE, which was during the rule of Constantine I. The text reads CRISPVS, which attributes the coin to Crispus, Constantine's eldest son who was executed at his father's orders. During his lifetime, Crispus led the Roman naval fleet and was the titular "leader" of Gaul.

Coin 046 Reverse

Because of the entrance of Christianity into the Roman empire during the time this coin was minted, it is valid to assume that coins would start to show Christian symbols; however, Constantine did not convert to Christianity until he was on his deathbed. Thus during his reign, coins like this secular image would be more common.

This coin depicts a guardian standing at the gates of a Roman castra. A castra is a Roman camp for soldiers. Roman legions would erect the camps during times of war when they would relocate for a battle. The figure is most likely guarding a castra during the Roman civil wars in the early 4th century. Christianity in Rome was not fully integrated yet, so the image is not religious. Instead, this reminds viewers of the military victories and power of the Roman Empire.

Page completed by Jessica Joshi, Rhodes College '25